Jerusalem

The New Testament says nothing about the death and burial of Mary, the Mother of Jesus, but a strong Christian tradition places her tomb in a dimly-lit church at the foot of the Mount of Olives.

The large crypt containing the empty tomb in the Church of the Assumption is all that remains of an early 5th-century church, making it possibly the oldest near-complete religious building in Jerusalem.

The location of the Tomb of Mary is across the Kidron Valley from St Stephen’s Gate in the Old City walls of Jerusalem, just before Gethsemane.

The Church of the Assumption stands partly below the level of the main Jerusalem-Jericho road. It is reached by a stairway leading down to an open courtyard.

Entry is through the façade of a 12th-century Crusader basilica that has been preserved intact. To the right, a passageway leads to the Grotto of Gethsemane.

Tomb resembles Holy Sepulchre

A wide Crusader stairway of nearly 50 steps leads to the crypt. Partway down, on the right, is a niche dedicated to the Virgin Mary’s parents, Anne and Joachim. This small chapel was originally the burial place of Queen Melisande, daughter and wife of Crusader kings of Jerusalem, who died in 1161.

Almost opposite is a niche dedicated to Mary’s husband, St Joseph. Here three women connected to Crusader kings were buried.

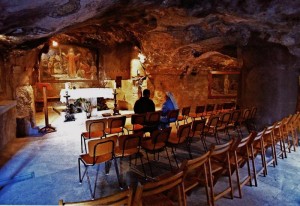

The crypt, much of it cut into solid rock, is dark and gloomy. The smell of incense fills the air, the ceiling is blackened by centuries of candle smoke, and gold and silver lamps hang in profusion.

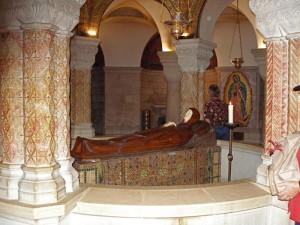

To the right, a small edicule houses a stone bench on which Mary’s body is believed to have lain. The edicule is richly decorated with Eastern Orthodox icons, candlesticks and flowers, but the interior is bare.

Narrow openings on two sides allow access, and three holes in the wall of the tomb enable pilgrims to touch the bench.

Because the emperor Constantine’s engineers cut away the surrounding rock to isolate the Tomb of Mary in the middle of the crypt, its appearance strongly resembles her Son’s tomb in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Floods in 1972 enabled excavations by the archaeologist Bellarmino Bagatti, who concluded that the place where Mary had been buried was clearly located in a cemetery used during the first century.

Several denominations share site

The church belonged to the Catholic Franciscans from 1363 until 1757. When they were expelled it passed into the hands of the Eastern Orthodox churches.

The Greek Orthodox Church now shares possession with the Armenian Orthodox. The Syriac Orthodox, the Coptic Orthodox and the Ethiopian Orthodox have minor rights.

Muslims also worship here. In the wall to the right of the Tomb of Mary is a mihrab niche giving the direction of Mecca. It was installed after Saladin’s conquest in the 12th century.

The place is holy to Muslims because they believe Muhammad saw a light over the tomb of his “sister Mary” during his Night Journey to Jerusalem.

Early writers describe death and burial

The New Testament may be silent on the end of Mary’s life, but several early apocryphal sources, such as Transitus Mariae, describe her death and burial in Jerusalem.

These works are of uncertain authenticity and not accepted as part of the Christian canon of Scripture.

But, according to biblical scholar Lino Cignelli, “All of them are traceable back to a single primitive document, a Judaeo-Christian prototype, clearly written within the mother church of Jerusalem some time during the second century, and, in all probability, composed for liturgical use right at the Tomb of Our Lady.

“From the earliest times, tradition has assigned the authorship of the prototype to one Lucius Carinus, said to have been a disciple and fellow labourer with St John the Evangelist.”

By the reckoning of Transitus Mariae, Mary would have been aged no more than 50 at the time of her death.

Ephesus claim not supported

A competing claim is made that the Virgin Mary died and was buried in the city of Ephesus, in present-day Turkey. This claim rests in part on the Gospel account that Christ on his cross entrusted the care of Mary to St John (who later went to Ephesus).

But the earliest traditions all locate the end of Mary’s life in Jerusalem, as the Catholic Encyclopedia recounts:

“The apocryphal works of the second to the fourth century are all favourable to the Jerusalem tradition. According to the Acts of St John by Prochurus, written (160-70) by Lencius, the Evangelist went to Ephesus accompanied by Prochurus alone and at a very advanced age, i.e. after Mary’s death.

“The two letters B. Inatii missa S. Joanni, written about 370, show that the Blessed Virgin passed the remainder of her days at Jerusalem. That of Dionysius the Areopagite to the Bishop Titus (363), the Joannis liber de Dormitione Mariae (third to fourth century), and the treatise De transitu B.M. Virginis (fourth century) place her tomb at Gethsemane . . . .

“There was never any tradition connecting Mary’s death and burial with the city of Ephesus.”

Assumption mentioned in early sources

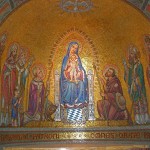

The name of the Church of the Assumption reflects the Christian belief that Mary was bodily assumed into heaven. This belief is mentioned in early apocryphal sources, as well as in authenticated sermons by Eastern saints such as St Andrew of Crete and St John of Damascus.

The Assumption of Mary has been a subject of Christian art for centuries (and its feast day was made a public holiday in England by King Alfred the Great in the 9th century). It was defined as a doctrine of the Catholic Church by Pope Pius XII in 1950.

The Eastern Orthodox churches celebrate the feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God on August 15, the same day that the Catholic Church celebrates the feast of the Assumption of Mary.

Related site:

Administered by: Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre

Tel.: 972-2-6284613

Open: 5am(6am Oct-Mar)-12 noon, 2.30–5pm

- Doorway to the Tomb of Mary (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

- Artwork at the Tomb of Mary (Seetheholyland.net)

- Mary’s empty tomb (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

- Church of the Assumption (Seetheholyland.net)

- Death of the Virgin, by Hugo van der Goes (Groeningemuseum, Brugge)

- Entering the Tomb of Mary (Svetlana Makarova)

- Lamps at the Tomb of Mary (Seetheholyland.net)

- Lamps and icons at the Tomb of Mary (Seetheholyland.net)

- Icon at the Tomb of Mary (Seetheholyland.net)

- Altar at the Tomb of Mary (Seetheholyland.net)

- Mary’s tomb under marble slab (Seetheholyland.net)

- Icon of Mary’s death at the Tomb of Mary (Seetheholyland.net)

- Steps down to the Tomb of Mary (Seetheholyland.net)

- Edicule over the Tomb of Mary (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

- Petitions and prayers in the Tomb of Mary (Seetheholyland.net)

- Entrance to Church of the Assumption (Seetheholyland.net)

- Inside the Tomb of Mary (Svetlana Makarova)

References

Bar-Am, Aviva: Beyond the Walls: Churches of Jerusalem (Ahva Press, 1998)

Cignelli, Lino: “Our Lady’s Tomb in the Apocrypha”, Holy Land, spring 2005.

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Gonen, Rivka: Biblical Holy Places: An illustrated guide (Collier Macmillan, 1987)

Inman, Nick, and McDonald, Ferdie (eds): Jerusalem & the Holy Land (Eyewitness Travel Guide, Dorling Kindersley, 2007)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Wareham, Norman, and Gill, Jill: Every Pilgrim’s Guide to the Holy Land (Canterbury Press, 1996)

External links