Jerusalem

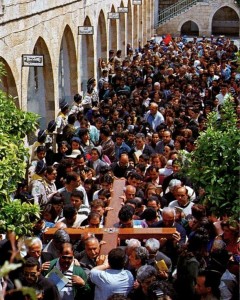

First Station: Pilgrims carry a cross through the courtyard of the Al-Omariyyeh College (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

Chapel of the Flagellation

Chapel of the Condemnation

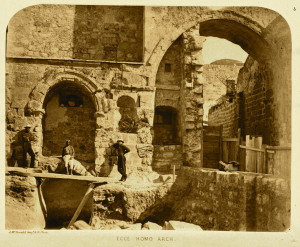

Ecce Homo Arch

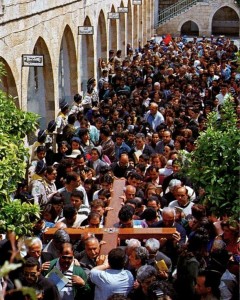

Every Friday afternoon hundreds of Christians join in a procession through the Old City of Jerusalem, stopping at 14 Stations of the Cross as they identify with the suffering of Jesus on his way to crucifixion.

Their route is called the Via Dolorosa (Way of Sorrows). This is also the name of the principal street they follow, a narrow marketplace abustle with traders and shoppers, most likely similar to the scene on the first Good Friday.

It is unlikely that Jesus followed this route on his way to Calvary. Today’s Via Dolorosa originated in pious tradition rather than in certain fact, but it is hallowed by the footsteps of the faithful over centuries.

Franciscans lead procession

First Station: Franciscan friars begin the Friday observance in the courtyard of the Al-Omariyyeh College (Seetheholyland.net)

The Friday procession is led by Franciscan friars, custodians of most of the holy places since the 13th century.

It starts at 4pm — 3pm in winter, from late October till late March — at an Islamic college, Umariyya School, just inside St Stephen’s or Lions’ Gate. Pilgrims wind their way westward to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, where the last five Stations are located.

Each procession is accompanied by escorts called kawas, in Ottoman uniforms of red fez, gold-embroidered waistcoat and baggy blue trousers, who signify their authority by banging silver-topped staves on the ground.

Many other pilgrims, individually or in groups with guides, follow the same 500-metre route during the week.

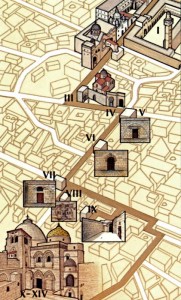

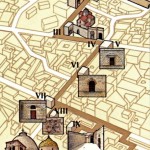

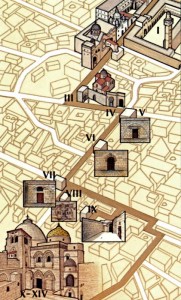

Route of the Via Dolorosa (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

For those walking the Via Dolorosa on their own, the route is not easy to follow.

A simple map is available from the Christian Information Centre, Omar Ibn el-Khattab Square, Jaffa Gate (closed on Sundays, Christian holidays and Saturday afternoons). The PlanetWare travel guide also has a map.

Number of Stations has varied

While scholars disagree on the path Jesus took on Good Friday, processions in the 4th and 5th centuries from the Mount of Olives to Calvary followed more or less along the route taken by modern pilgrims (but there were no stops for Stations).

The practice of following the Stations of the Cross appears to have developed in Europe among Christians who could not travel to the Holy Land. The number of Stations varied from 7 to 18 or more.

Today’s Via Dolorosa route was established in the 18th century, with the present 14 Stations, but some of the Stations were given their present location only in the 19th century.

Bronze discs mark Stations on the Via Dolorosa; the crossed arms are a Franciscan symbol (Seetheholyland.net)

Nine of the 14 stations are based on Gospel references. The other five — Jesus’ three falls, his meeting with his Mother, and Veronica wiping his face — are traditional.

Place of judgement unknown

The chief difficulty in determining Jesus’ path to Calvary is that nobody knows the site of Pontius Pilate’s Praetorium, where Jesus was condemned to death and given the crossbeam of his cross to carry through the streets.

There are three possible locations:

• Herod the Great’s Palace or Citadel, which dominated the Upper City. The remains of the Citadel complex, with its Tower of David (erected long after King David’s time), are just inside the present Jaffa Gate. This is the most likely location.

Second Station: Ecce Homo Arch over Via Dolorosa, with Sisters of Zion convent at right (Seetheholyland.net)

• The Antonia Fortress, a vast military garrison built by Herod the Great north of the Temple compound and with a commanding view of the Temple environs. The Umariyya School, now the location of the first Station of the Cross, is believed to stand on part of its site.

• The Palace of the Hasmoneans, built before Herod’s time to house the rulers of Judea. It was probably located midway between Herod’s Palace and the Temple, in what is today the Jewish Quarter.

In the immediate area of the Antonia Fortress is the Ecce Homo Arch, reaching across the Via Dolorosa. It is named after the famous phrase (“Behold the Man” in Latin) spoken by Pilate when he showed the scourged Jesus to the crowd (John 19:5). But the arch was built after Jesus stood before Pilate.

Adjacent to the arch is the Ecce Homo Convent of the Sisters of Our Lady of Zion (the entrance is near the corner of the Via Dolorosa and a narrow alley called Adabat el-Rahbat, or The Nuns Ascent).

Second Station: Roman soldiers’ game in Lithostrotos pavement under Zion Sisters convent (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

Underneath the convent, pilgrims can visit stone pavings which were once claimed to be the Stone Pavement (Lithostrotos) where Pilate had his judgement seat (John 19:13).

Markings in the paving stones, indicating a dice game known as the King’s Game, suggested this was where Jesus was mocked by the soldiers (John 19:2-3). Yet this pavement is also from a later date.

Chapels worth visiting

Several of the chapels at the various Stations of the Cross are not often open to the public. Two at the beginning of the Via Dolorosa are open daily (8-12am, 2-5pm) and are worth visiting before starting the Way of the Cross.

Across the street from Umariyya School is a Franciscan compound containing the Chapel of the Flagellation and the Chapel of the Condemnation and Imposition of the Cross.

Second Station: Jesus takes up his cross, in Chapel of the Condemnation (Tom Callinan/Seetheholyland.net)

The Chapel of the Flagellation is notable for its stained-glass windows behind the altar and on either side of the sanctuary. They show Pilate washing his hands; Jesus being scourged; and Barabbas expressing joy at his release. On the ceiling above the altar, a mosaic on a golden background depicts the crown of thorns pierced by stars.

The Flagellation Museum, displaying archaeological artifacts from several Holy Land sites, including Nazareth, Capernaum and the Mount of Olives, is open daily (except Sunday and Monday), 9am-1pm and 2-4pm.

The Chapel of the Condemnation and Imposition of the Cross is topped by five white domes. Artwork includes papier-mâché figures enacting some of the events of Jesus’ Passion.

Paving stones at the back of the chapel are part of the pavement that extends under the Ecce Homo Convent.

Third Station: Relief depicting Jesus’ first fall (Seetheholyland.net)

Opposite the chapel entrance is a model of Jerusalem in the first century AD, showing how the sites of Calvary and the Holy Sepulchre were outside the city walls.

The 14 Stations

Numbering of the Stations of the Cross along the Via Dolorosa traditionally uses Roman numerals, and in 2019 bronze sculptures were added to depict what is commemorated at each station:

I: Jesus is condemned to death

Fourth Station: Sculpture depicting Jesus meeting his Mother (Seetheholyland.net)

About 300 metres west of St Stephen’s or Lions’ Gate, steps lead up to the courtyard of Umariyya School (open Monday-Thursday and Saturday, 2.30-6pm, Friday 2.30-4pm; entry with caretaker’s permission).

Here the First Station is commemorated. The southern end of the courtyard offers a view overlooking the Temple Mount.

II: Jesus carries his cross

Across the street, near where an arch stretches over the Via Dolorosa, the Second Station is marked by the words “II Statio” on the wall of the Franciscan Friary.

III: Jesus falls the first time

Down the Via Dolorosa, under the Ecce Homo Arch and about 100 metres along, a sharp left turn into Al-Wad Road brings pilgrims to a small chapel on the left, belonging to the Armenian Catholic Patriarchate.

Fifth Station: Pilgrims on the Way of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

Above the entrance, a stone relief of Jesus falling with his cross marks the Third Station. Inside, a similar image is watched by shocked angels.

IV: Jesus meets his Mother

The Fourth Station is now commemorated adjacent to the Third Station. Until 2008 this Station was commemorated a further 25 metres along Al-Wad Road.

The stone relief marking the Station is over the doorway to the courtyard of an Armenian Catholic church. In the crypt are a strikingly attractive adoration chapel and part of a mosaic floor from a 5th-century church. In the centre of the mosaic is depicted a pair of sandals, said to represent the spot where the suffering Mary was standing.

Sixth Station: Column imbedded in wall recalls tradition that Veronica wiped Jesus’ face here (Seetheholyland.net)

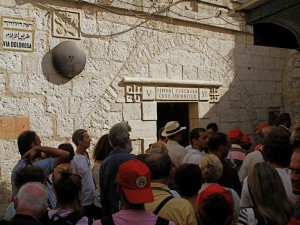

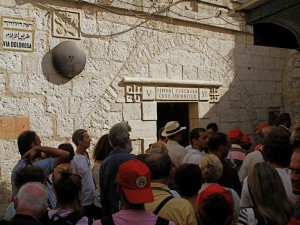

V: Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus carry his cross

About 25 metres further along Al-Wad Road, the Via Dolorosa turns right. At the corner, the lintel over a doorway bears a Latin inscription marking the site where Simon, a visitor from present-day Libya, became involved in Jesus’ Passion.

The Franciscan chapel here, dedicated to Simon the Cyrenian, is on the site of the Franciscans’ first house in Jerusalem, in 1229.

VI: Veronica wipes the face of Jesus

The Via Dolorosa now becomes a narrow, stepped street as it wends its way uphill. About 100 metres on the left, a wooden door with studded metal bands indicates the Greek Catholic (Melkite) Church of St Veronica.

According to tradition, the face of Jesus was imprinted on the cloth she used to wipe it. A cloth described as Veronica’s veil is reported to have been kept in St Peter’s Basilica in Rome since the 8th century.

VII: Jesus falls the second time

Seventh Station: Relief depicting Jesus’ second fall, in one of the chapels at the Station (Seetheholyland.net)

About 75 metres further uphill, at the junction of the Via Dolorosa with Souq Khan al-Zeit, two Franciscan chapels, one above the other, mark the Seventh Station.

Inside the lower chapel is a large stone column, part of the colonnaded Cardo Maximus, the main street of Byzantine Jerusalem, which ran from north to south.

The position of this Station marks the western boundary of Jerusalem in Jesus’ time. It is believed he left the city here, through the Garden Gate, on his way to Calvary.

VIII: Jesus consoles the women of Jerusalem

Across Souq Khan al-Zeit and about 20 metres up a narrower street, the Eighth Station is opposite the Station VIII Souvenir Bazaar.

On the wall of a Greek Orthodox monastery, beneath the number marker is a carved stone set at eye level. It is distinguished by a Latin cross flanked by the Greek letters IC XC NI KA (meaning “Jesus Christ conquers”).

Eighth Station: Stone in wall, carved with Latin cross (Seetheholyland.net)

IX: Jesus falls the third time

Now it is necessary to retrace one’s steps back towards the Seventh Station, and turn right along Souq Khan al-Zeit.

Less than 100 metres on the right is a flight of 28 wide stone steps. At the top, a left turn along a winding lane for about 80 metres leads to the Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate, where the shaft of a Roman pillar to the left of the entrance marks Jesus’ third fall. Nearby is the Coptic Chapel of St Helen.

To the left of the pillar, three steps lead to a terrace that is the roof of the Chapel of St Helena in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Here, in a cluster of primitive cells, live a community of Ethiopian Orthodox monks.

X: Jesus is stripped of his garments

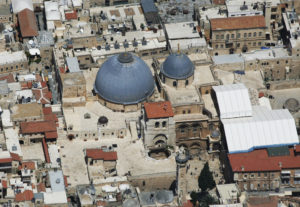

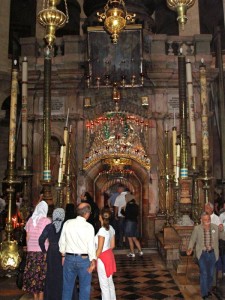

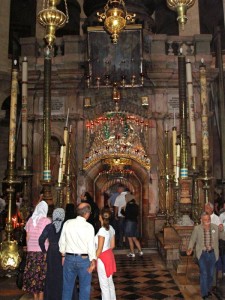

The last five Stations of the Cross are situated inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Ninth Station: Roman pillar in far corner marks Jesus’ third fall (Seetheholyland.net)

If the door to the roof of the church is open, a short cut is possible.

On the terrace, the second small door on the right leads into the Ethiopians’ upper chapel. Steps at the back descend to their lower chapel, where a door gives access to the courtyard of the Holy Sepulchre basilica.

The Friday procession, however, returns along the winding lane and stone steps to Souq Khan al-Zeit, turning right after about 40 metres into Souq al-Dabbagha.

After about 80 metres, bearing to the right, a small archway with the words “Holy Sepulchre” leads into the church courtyard.

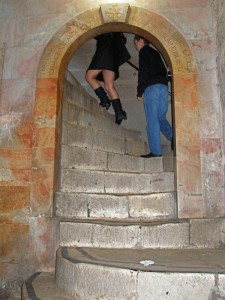

To the right inside the main door of the church, 19 steep and curving steps lead up to the chapels constructed above the rock of Calvary.

The five Stations inside the church are not specifically marked.

Tenth Station: Interior of Chapel of the Franks, where the Tenth Station is located (Seetheholyland.net)

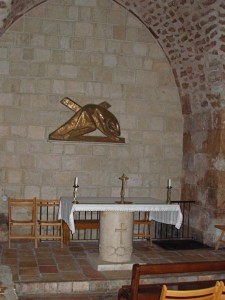

After ascending the steps inside the door, immediately on the right is a window looking into a small worship space called the Chapel of the Franks (a name traditionally given to the Franciscans). Here, in what was formerly an external entrance to Calvary, the Tenth Station is located.

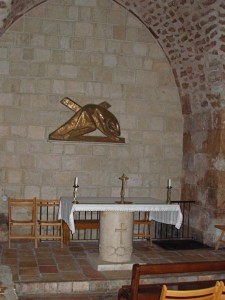

XI: Jesus is nailed to the cross

The Catholic Chapel of the Nailing to the Cross, in the right nave on Calvary, is the site of the Eleventh Station.

On its ceiling is a 12th-century medallion of the Ascension of Jesus — the only surviving Crusader mosaic in the church.

Eleventh Station: Catholic chapel on Calvary floor commemorates the nailing of Jesus to the cross (Seetheholyland.net)

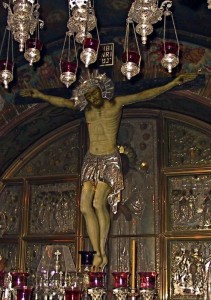

XII: Jesus dies on the cross

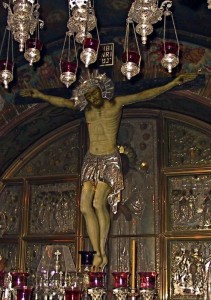

The much more ornate Greek Orthodox Chapel of the Crucifixion, in the left nave of Calvary, is the Twelfth Station.

A silver disc beneath the altar marks the place where it is believed the cross of Christ stood. The limestone rock of Calvary may be touched through a round hole in the disc.

XIII: Jesus is taken down from the cross

Between the Catholic and Greek chapels, a Catholic altar of Our Lady of Sorrows, depicting Mary with a sword piercing her heart, commemorates the Thirteenth Station.

XIV: Jesus is laid in the tomb

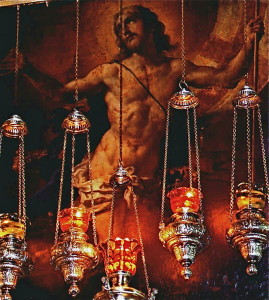

Twelfth Station: Close-up of figure of Christ in Chapel of the Crucifixion (Picturesfree.org)

Another flight of steep stairs at the left rear of the Greek chapel leads back to the ground floor.

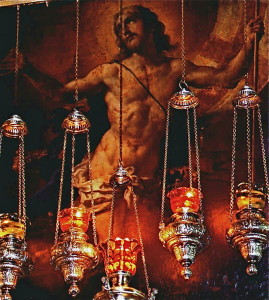

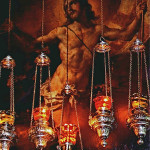

Downstairs and to the left, under the centre of the vast dome of the church, is a stone monument called an edicule (“little house”), its entrance flanked by rows of huge candles.

This is the Tomb of Christ, the Fourteenth Station of the Cross.

This stone monument encloses the tomb (sepulchre) where it is believed Jesus lay buried for three days — and where he rose from the dead on Easter Sunday morning.

Related articles:

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Church of the Holy Sepulchre Chapels

Fourteenth Station: Edicule over the Tomb of Jesus (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

In Scripture:

The crucifixion: Matthew 27:24-61; Mark 15:15-47; Luke 23:24-56; John 18:13—19:42

Resurrected Christ behind ornate lamps above the door of the edicule (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

The empty tomb: Matthew 28:1-10; Mark 16:1-8; Luke: 24:1-12; John 20:1-10

Administered by: Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land

Tel.: 972-2-6272692

-

-

Muslim escorts at Good Friday procession (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Bronze discs mark Stations on the Via Dolorosa; the crossed arms are a Franciscan symbol (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Pilgrims on the Via Dolorosa (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Route of the Via Dolorosa (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

First Station: Franciscan friars begin the Friday observance in the courtyard of the Umariyya School (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

First Station: Courtyard of Umariyya School, where Friday procession begins (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

First Station: Pilgrims carry a cross through the courtyard of the Umariyya School (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Second Station: Ecce Homo Arch over Via Dolorosa, with Sisters of Zion convent at right (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Second Station: Pilgrims at Chapel of the Flagellation (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

-

-

Second Station: Model of old Jerusalem outside Chapel of the Condemnation. It shows Third Wall at right and Calvary and the Tomb of Christ in upper centre, outside Second Wall (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Second Station: Grounds of the Chapel of the Condemnation (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Second Station: Jesus is condemned, a tableau in Chapel of the Condemnation (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Second Station: Jesus takes up his cross, in Chapel of the Condemnation (Tom Callinan/Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Second Station: Stained-glass window in Chapel of the Flagellation (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Second Station: Crown of thorns in dome of Chapel of the Flagellation (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Second Station: Chapel of the Condemnation (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Second Station: Entrance to Chapel of the Flagellation, with the Chapel of the Condemnation behind it (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Second Station: Part of Ecce Homo Arch (right) in wall of Sisters of Zion chapel (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

-

-

Second Station: Roman soldiers’ game in Lithostrotos pavement under Zion Sisters convent (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Second Station: Mosaic of Jesus beside an ancient Roman pavement, the Lithostrotos, under Sisters of Zion convent (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Second Station: Franciscan friars at the Station marker (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Second Station: Entrance to Chapel of the Flagellation, with the Chapel of the Condemnation behind it (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Third Station: Shocked angels look on the fallen Jesus, in the Third Station chapel (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Third Station: Franciscan flag above pilgrims’ heads (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Third Station: Relief depicting Jesus’ first fall (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Fourth Station: Sculpture depicting Jesus meeting his Mother (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Fourth Station: Bronze disk marker (James Emery)

-

-

Fourth Station: Armenian Catholic church (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Fourth Station: Relief depicting Jesus meeting his Mother (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Fourth Station: Mary’s sandals in 5th-century mosaic floor (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Fourth Station: Graphic representation of the fallen Jesus in the Armenian church (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Fourth Station: Armenian Catholic adoration chapel (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Fifth Station: Door lintel records Simon of Cyrene’s carrying of the cross (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Fifth Station: Pilgrims on the Way of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Fifth Station: Stone in wall, said to bear the imprint of Jesus’ hand (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Fifth Station: Relief showing Simon of Cyrene helping to carry the cross (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Sixth Station: Friday procession stops to pray (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Sixth Station: Close-up of column in wall (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Seventh Station: Relief depicting Jesus’ second fall, in one of the chapels at the Station (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Seventh Station: Franciscan friar leads prayers (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Seventh Station: Altar in one of the chapels at the Station (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Seventh Station: This was on the western boundary of the city in Jesus’ time (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Seventh Station: Roman column at the western boundary of Jerusalem in Jesus’ time (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Eighth Station: Stone in wall, carved with Latin cross (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Eighth Station: Close-up of stone, with Greek initials meaning “Jesus Christ conquers” (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Ninth Station: Roman pillar in far corner marks Jesus’ third fall (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Ninth Station: Pilgrims outside Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Ninth Station: Coptic Orthodox Chapel of St Helen (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Church of the Redeemer bell tower seen from the roof of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Ninth Station: Ethiopian Orthodox Chapel of St Anthony provides short cut to Holy Sepulchre Church (Tom Callinan / Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Parvis (courtyard) of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Tenth Station: Chapel of the Franks at top of steps, now closed. (© Deror Avi)

-

-

Tenth Station: Abraham preparing to kill Isaac, mosaic above window to Chapel of the Franks (Caleb Zahnd)

-

-

Tenth Station: Interior of Chapel of the Franks (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Eleventh Station: Catholic chapel on Calvary floor commemorates the nailing of Jesus to the cross (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Eleventh Station: Mosaic in Catholic Chapel of the Nailing to the Cross Eleventh Station: Close-up of mosaic of Jesus nailed to the cross (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Twelfth Station: Greek Orthodox Chapel of the Crucifixion Twelfth Station: Greek Orthodox Chapel of the Crucifixion (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Twelfth Station: Close-up of crucifix in Chapel of the Crucifixion Twelfth Station: Close-up of figure of Christ in Chapel of the Crucifixion (Picturesfree.org)

-

-

Twelfth Station: Close-up of face of Virgin Mary in Chapel of the Crucifixion (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Twelfth Station: Disc marking traditional place where Jesus’ cross stood, in Chapel of the Crucifixion (c Adriatikus)

-

-

Thirteenth Station: Catholic altar of Our Lady of Sorrows Thirteenth Station: Chapel of Our Lady of Sorrows (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Fourteenth Station: Front of edicule over the Tomb of Christ (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Rolling-stone tomb of the type in which Jesus was buried (Biblicalisraeltours.com)

-

-

The resurrected Christ, a painting hanging above the entrance to the edicule (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

References

Bar-Am, Aviva: Beyond the Walls: Churches of Jerusalem (Ahva Press, 1998)

Beitzel, Barry J.: Biblica, The Bible Atlas: A Social and Historical Journey Through the Lands of the Bible (Global Book Publishing, 2007)

Brownrigg, Ronald: Come, See the Place: A Pilgrim Guide to the Holy Land (Hodder and Stoughton, 1985)

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Gonen, Rivka: Biblical Holy Places: An illustrated guide (Collier Macmillan, 1987)

Hibbs, Jon: “Jerusalem: Pilgrims and Playboys”, The Telegraph, April 3, 1999

Jacobs, Daniel: Jerusalem: The Mini Rough Guide (Rough Guides, 1999)

Mackowski, Richard M.: Jerusalem: City of Jesus (William B. Eerdmans, 1980)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: Keys to Jerusalem (Oxford University Press, 2012)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Pixner, Bargil: With Jesus in Jerusalem – his First and Last Days in Judea (Corazin Publishing, 1996)

Walker, Peter: In the Steps of Jesus (Zondervan, 2006)

Zohar, Gil: “X Marks the Spot”, Associated Christian Press Bulletin, January-February 2009

External links

Flagellation (Custodia Terrae Sanctae)