The practice of venerating relics of holy people is common to many faiths. For most Christians, physical objects associated with Jesus Christ or a saint have special significance and perhaps even healing power.

The Gospels tell of people being cured by touching Jesus’ cloak (Matthew 9:20-22, Mark 6:56). The Acts of the Apostles says Paul’s handkerchiefs healed the sick (Acts 19:11-12).

The earliest Christian communities would have treasured any reminder of their Saviour, but a flood of fake relics into Europe during the Crusades caused a general scepticism towards Christian relics.

Artefacts of the Crucifixion — fragments of the True Cross, Crown of Thorns and Nails, genuine or spurious — competed with a claimed feather from the archangel Gabriel’s wing, Noah’s axe, wine from the wedding feast of Cana, and hair of the Virgin Mary.

“What lies there are about relics!” Martin Luther declared.

He surmised that “one could build a whole house using all the parts of the True Cross found scattered throughout the world”. But when 19th-century French architect Charles Rohault de Fleury catalogued all known fragments he found they totalled only 4000 cubic centimeters — less than 3 per cent of the likely volume of the Cross.

In the 21st century, Polish journalist Grzegorz Górny and photographer Janusz Rosikoń spent two years investigating Christ’s relics for their book Witnesses to Mystery.

“Almost everywhere we went,” Górny said, “we were confronted with the same remarkable phenomenon: these relics seemed to attract the attention of academics more than that of religious devotees.”

Many purported relics of Jesus may be genuine, though their authenticity is impossible to prove. This article looks at some that have been subjected to scientific scrutiny.

Shroud of Turin

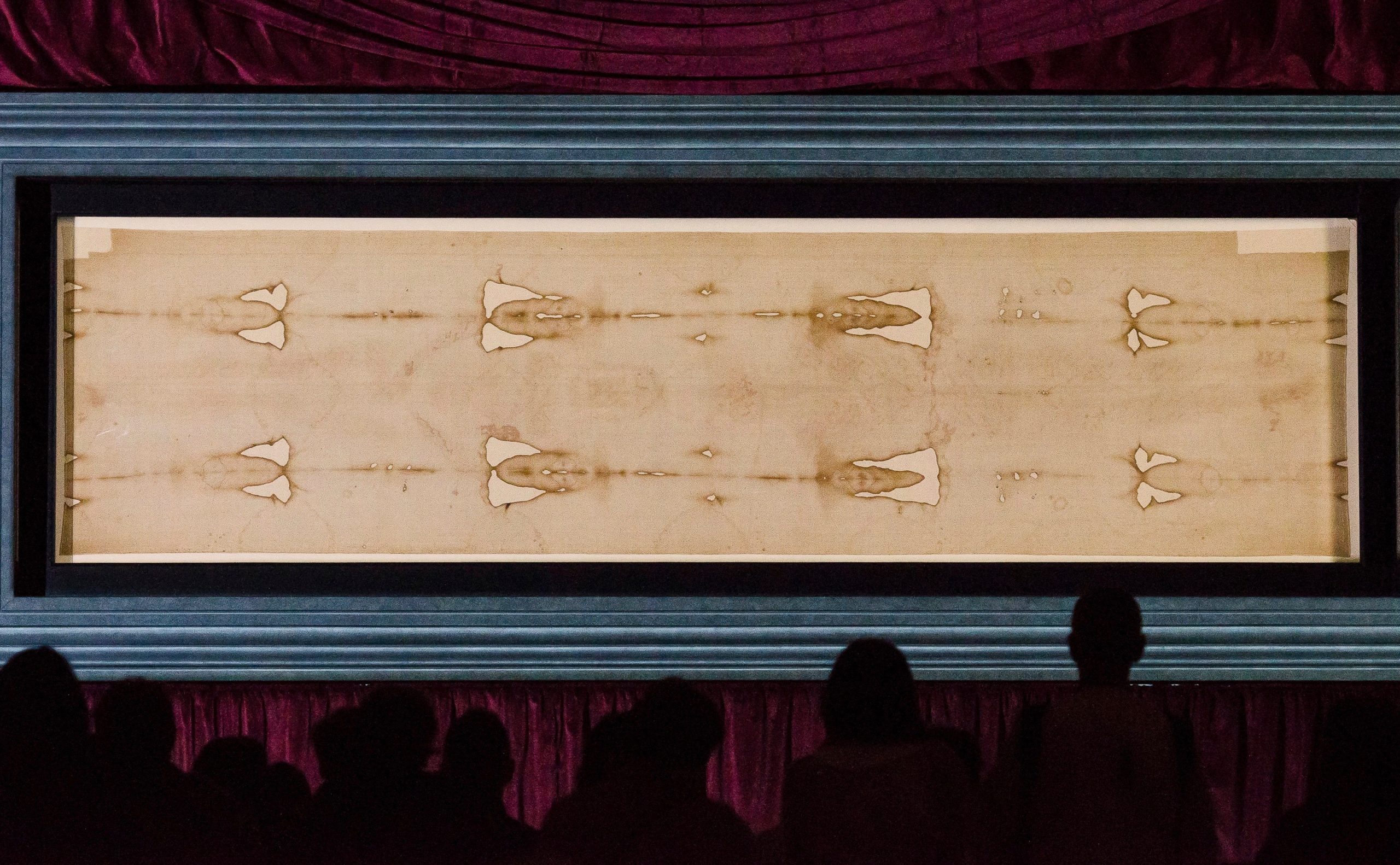

The Shroud of Turin, held in a chapel behind the Turin Cathedral, is the most scientifically studied religious relic in history. But science has been unable to prove whether it is the burial cloth of Jesus, with his image etched on its fibres at his Resurrection, or an ingenious medieval forgery.

Pilgrims viewing the Shroud of Turin during an exposition in 2015 (Stefano Guidi / Shutterstock)

The full-length image corresponds in many ways with the circumstances of Christ’s death as described in the Gospels. It depicts a muscular man of about 180cm and 77kg, who had been flogged, crowned with thorns, crucified by being nailed through the wrists, and wounded in the right chest.

The earliest mention of a cloth bearing the image of Jesus was by the Christian historian Eusebius of Caesarea (c.260-339), who said it was in Edessa (now the Turkish city of Urfa) at the court of the Arab King Abgar V, who died in AD 40 after reputedly converting to Christianity. There are later indications of its presence in Antioch, Cilicia, Cappadocia, Constantinople and Athens.

The first documented exposition of the cloth now held in Turin was at Lirey, in northern France, in 1355. It was sold to the Duke of Savoy in 1453 and moved to Turin in 1578. In 1983 it was donated to the Holy See, the episcopal jurisdiction of the Pope.

In 1532, while in Chambery, capital of the Savoy region of France, parts of the Shroud were charred in a chapel fire. Local nuns mended the damaged areas.

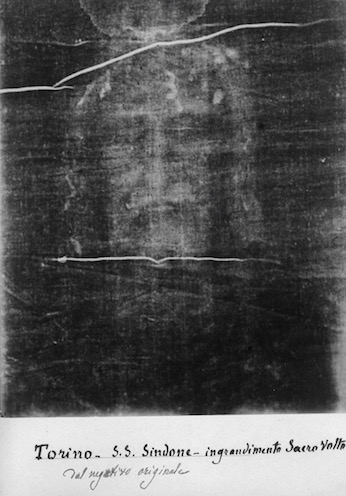

In 1898 Italian photographer Secondo Pia discovered that the image on the Shroud is in the form of a photographic negative. Every effort using modern technologies to produce an image with the same physical and chemical characteristics has failed.

Original negative of Italian photographer Secondo Pia in 1898 (Musée de l’Élysée, Lausanne)

Comprehensive research was carried out in 1978 by the Shroud of Turin Research Project team, which reported: “We can conclude for now that the Shroud image is that of a real human form of a scourged, crucified man. It is not the product of an artist. The blood stains are composed of haemoglobin and also give a positive test for serum albumin. The image is an ongoing mystery . . . .”

Most of the pollen grains found on the Shroud are from plants that grew in Judea. Mineral particles are of argonite, used in buildings of old Jerusalem.

The blood cells are from the rare AB group, more often found in Jews. But there is no image beneath the blood stains — so the blood was deposited before the image was formed.

How a man’s image could be imprinted on both sides of a cloth, at a depth of only about 200 nanometres, still puzzles scientists.

After five years of testing, Italian scientists from the National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development concluded in 2011 that it could only be the effect of an enormous discharge of electromagnetic energy in a very short amount of time — something like a flash of light.

“We have shown that a short burst of high-intensity ultraviolet light gives a linen colouration which overlaps much better with the microscopic characteristics of the Shroud image, compared to the colouration obtained thus far by chemical ‘contact’ methods like paints, acids and powders.”

However, they added, the ultraviolet radiation needed to instantly colour a cloth the size of the Shroud would require the power of 34 thousand billion watts — many thousand times more powerful than any modern source could provide.

Full-length negative of the front image on the Shroud (Wikipedia)

In 1988 Church authorities permitted a small piece to be cut from a corner of the Shroud for radiocarbon dating. Tests carried out in Oxford, Zurich and Arizona, under the auspices of the British Museum, dated the cloth to AD 1260-1390 — suggesting the Shroud was a medieval forgery.

While this result appeared conclusive, other scientists questioned it on several grounds. These included:

● The 81mm by 16mm sample was taken from only one area, a corner where it had been held up by unwashed hands for public exhibitions over the centuries.

● In 2005 American chemist Raymond Rogers claimed this area contained almost indistinguishable cotton threads from the mending by nuns after the 1532 fire. Swiss textile restorer Mechthild Flury-Lemberg, who had carried out conservation work on the Shroud, said this was not so, but “The presence of the greasy dirt deposit at the ‘removal site’ alone would be sufficient to demonstrate the uselessness of the carbon-14 method, without having to construct an untenable ‘mending theory’.”

● The porous nature of textiles such as linen, especially those frequently handled and exposed to human influences — make it difficult to find samples that have never been in contact with polluting materials. The Shroud’s fibres are dirty and heavily polluted by dust, burned shards, mucilage, mildew, spores, mites, and fungi.

● Raw data from the 1988 tests was never released, despite numerous requests from scholars. Then French researcher Tristan Casabianca in 2017 used a Freedom of Information action to obtain data from the British Museum. A two-year analysis by a French-Italian team found the 1988 results were unreliable.

The director of the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, Professor Christopher Ramsey, acknowledged in 2008: “There is a lot of other evidence that suggests to many that the Shroud is older than the radiocarbon dates allow and so further research is certainly needed.”

Research to measure the natural ageing of textile cellulose and convert it to time since manufacture was reported in 2022 by Dr Liberato de Caro at the Italian National Research Council’s Institute of Crystallography.

He tested the Shroud against a variety of samples of historical textiles documented to be aged from 3000 BC to AD 2000. The Shroud best matched a piece of fabric known to have come from the siege of Masada, Israel, in AD 55-74.

Veil of Manoppello

A church in the village of Manoppello, in Italy’s Abruzzo province, displays a cloth with an image that bears a striking resemblance to the face on the Turin Shroud.

Unlike the Shroud’s image of a dead man, with eyes closed, the Veil of Manoppello shows the face of a living man, his open eyes engaging the viewer with a steady gaze.

Sixth-century sources locate such a cloth in the town of Camulia, near Edessa. In 574 the emperor Justin II moved it to Constantinople.

Believed to be one of the burial cloths of Jesus, it was adopted as the imperial standard and even taken into battle. Its image became the model for Christ’s face on Byzantine coins.

Around 700 Patriarch Kallinikos I of Constantinople took the cloth to Rome. Displayed in the old St Peter’s Basilica, it became the most popular pilgrimage attraction in medieval Rome and was referred to by Petrarch and Dante.

It became known as the Veronica, after the name of a woman in the devotional Stations of the Cross. On the way to Calvary, she reputedly wiped the face of Jesus and had his image imprinted on her cloth — an incident not recorded in the Gospels. The name given the woman derives from the Latin adjective vera (true) and Greek noun eikon (image).

In the 16th century the cloth mysteriously disappeared. An empty frame, with broken glass, remained in the Vatican treasury and an indistinct replica was displayed once a year in the new St Peter’s.

By 1638 the cloth had reappeared in Manoppello, where it is kept in a glass monstrance above the main altar in the Capuchin church and may be viewed from both sides.

Image on the Veil of Manoppello (ElfQrin / Wikipedia)

The lifesize image is of a bruised face, curled sideburns, wisps of hair in the middle of a high forehead, and a thin beard forked in two. Every change of angle or lighting gives a different appearance.

“In person, it changes like a rainbow and seems to combine traits of holograms, photographs, paintings, and drawings,” writes journalist Grzegorz Górny.

The 17cm by 24cm cloth is of very thin byssus, a rare and expensive fibre known in ancient times as “silk from the sea” and obtained from mother-of-pearl. Scientists have found there are no traces of paint, rather the image results from modification of the fabric’s fibres and has a three-dimensional character.

Experts say intrusive scientific examination of the Veil is not possible because it would probably fall apart if it were removed from the two panes of lead glass where it has been stuck for centuries — and contamination from lead oxide in the glass could distort results.

While the Shroud of Turin is a photographic negative, the image on the Veil of Manoppello is positive. But scientists who have compared the two images have remarked on their similarity.

When Professor Andreas Resch, of the Institute for the Field Limits of Science in Innsbruck, overlaid high-definition prints of both images he concluded they showed “a 100 per cent match”.

“We can give only one explication of the perfect superimposition: the Veil of Manoppello and the Holy Shroud of Turin were in the same place,” he said.

There is one enigmatic difference that no scientist can explain: Although the cloth is transparent, the lock of hair in the middle of the forehead appears differently on each side.

Professor Jan S. Jaworski, of the University of Warsaw, and Professor Giulio Fanti, of the University of Padua, see this as “one of the particularities that speak in favour of the hypothesis of an Acheropita image” — meaning an image made without human hands.

They said their comparative study of the Veil and the Shroud also corroborated “the hypothesis that both images represent the face of the same tortured body”.

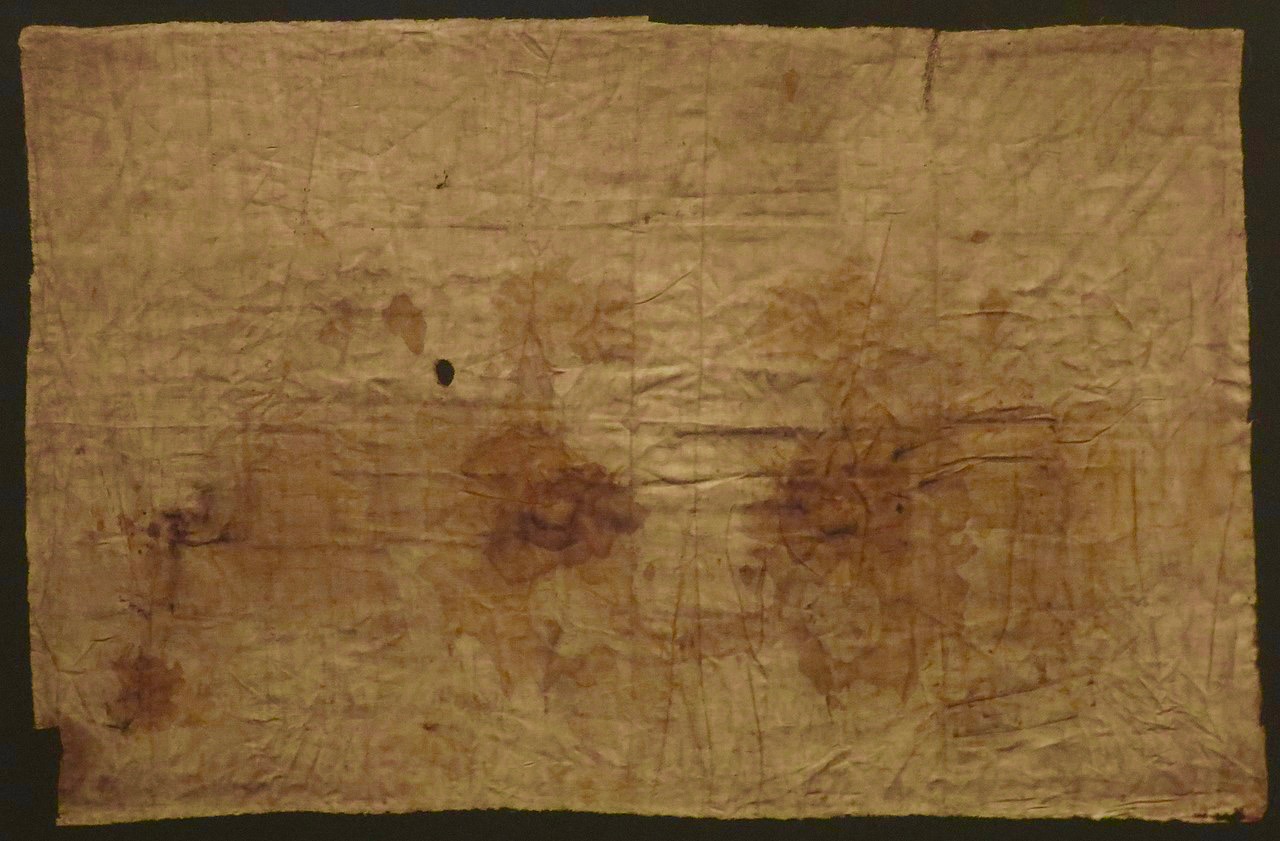

Sudarium of Oviedo

A crumpled piece of cheap linen with bloodstains but no image is kept in the Cathedral of Oviedo, in north-west Spain. It is believed to have been wrapped around Jesus’ head after he died, before Pontius Pilate gave permission for his body to be taken down from the cross.

The Sudarium — Latin for sweat cloth — would therefore be “the cloth that had been on Jesus’ head . . . rolled up in a place by itself” that was found in the empty tomb after the Resurrection, as described in John 20:7.

Tests on the Sudarium and the Shroud of Turin have found that the blood on both relics is of the same AB type.

Radiocarbon dating has placed the 84cm by 53cm cloth at around AD 700. Since it is first mentioned 130 years earlier by Antoninus of Piacenza, the radiocarbon result emphasises the difficulty of dating woven fabrics.

Sudarium of Oviedo (Reinhard Dietrich / Wikipedia)

Antoninus in AD 570 wrote that the Sudarium was being cared for in a cave near the monastery of St Mark at Jerusalem. Later manuscripts trace its movements from Jerusalem to Alexandria, Cartagena, Seville and Toledo. It has been in Oviedo since the 11th century.

According to Dr Alfonso Sánchez Hermosilla, medical examiner for the Spanish Sindonology Research Centre Team: “From the forensic anthropology and forensic medicine point of view, all the information discovered by the scientific research is compatible with the hypothesis that the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo covered the corpse of the same person.”

The most detailed research was carried out by a Valencia-based group, including specialists in criminology and haematology, in 1989. It concluded that the cloth covered the head of a body that had “died in conditions totally compatible with those of crucifixion”, and that stains caused by sharp objects on the nape of the neck were consistent with the head being crowned with thorns.

In Jewish custom such a cloth would have been wrapped around the head after Jesus’ death to absorb blood from his nose and mouth. Then it would have been placed in the tomb with the body.

X-ray fluorescence testing has found dirt on the Sudarium similar to samples from the site of Calvary. Pollen grains endemic to the Mediterranean region were identified, three of them found only in Palestine. Traces of myrrh and aloe, used in anointing corpses, were also noted.

Tunic of Argenteuil

A tattered and bloodstained woollen garment, woven without seams, is preserved in the Basilica of St Denis in Argenteuil, a north-western suburb of Paris.

Is this the “seamless tunic” of Jesus referred to in the Gospel of John (19:23), for which the Roman soldiers cast lots at the Crucifixion?

After vague references to it in the 5th and 6th centuries, the Tunic of Argenteuil is believed to have been obtained by the emperor Charlemagne, who bequeathed it before he died in 814 to the Benedictine convent in Argenteuil, where his daughter Theodrada was abbess.

Around 850 the convent was destroyed in a Norman invasion, but before then the Tunic had been walled up in a special hiding place with letters in French and Latin attesting to its origin. The garment and letters were rediscovered in 1156.

In 1793 the parish priest of Argenteuil cut the Tunic into several pieces, each hidden in a different place, to prevent its complete destruction during the French Revolution. Most of the pieces were later recovered and sewn together with a reinforcing lining.

Restoration was undertaken in 2015, when the garment was sewn on to a paler woollen cloth.

Tunic of Argenteuil (Shroud.com)

The tunic measures one metre across and is just under a metre long. It is woven from sheep’s wool, dyed purple-brown by a mixture of madder (a plant found in the Mediterranean region) and a mordant of iron.

In 1998 scientists from the Optics Institute in Paris found the bloodstains on the Tunic coincided with the wounds visible on the Shroud of Turin. The AB blood type is the same as on the Shroud and the Sudarium of Oviedo.

In 2004 further investigations were undertaken by French scientists Professor André Marion and Professor Gérard Lucotte, founders of the Institute of Genetic Molecular Anthropology in Paris.

Using scientific imaging equipment, Professor Marion mapped the bloodstains and found the most bloodied areas were in a 20cm strip from the left shoulder to the middle of the back, suggesting they were made by a long and heavy object that pressed against the wearer’s back.

Professor Lucotte found traces of urea, a constitutive element of perspiration, in the blood. He said these indicated the rare condition of haematidrosis, in which extreme stress causes a person to sweat blood. The Gospel of Luke (who was a doctor) records that Jesus sweated drops of blood in the Garden of Gethsemane (22:44).

The scientists found pollen grains belonging to several plant species already discovered on the Turin Shroud or Sudarium of Oviedo.

The Tunic was radiocarbon dated in 2004 and 2005, the results indicating the periods of AD 530-650 and AD 670-880. Supporters of the Tunic see these results — as with the carbon dating of the Shroud and the Sudarium — as further indications of the difficulty of dating woven fabrics, which easily absorb contaminating substances.

Furthermore, if the radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin (to AD 1260-1390), the Sudarium of Oviedo (to around AD 700) and the Tunic of Argenteuil (to AD 530-880) are all accurate, then it must be assumed that three highly sophisticated forgeries were produced over a period of hundreds of years during the Middle Ages, all consistent in blood type, arrangement of wounds and presence of pollen grains.

True Cross

Of all the reputed relics of Jesus, the best-known are fragments believed to be from the True Cross. Scores of these are venerated in churches around the world.

The largest (63.5cm by 39.3cm and 3.8cm thick) is in the Monastery of Saint Toribio De Liébana near Potes in northern Spain. Another large piece (over 42cm long) is in St Mark’s Basilica in Venice.

Reputedly the largest surviving piece of the True Cross, in Monastery of Saint Toribio De Liébana, Spain (Francisco J. Díez Martí / Wikipedia)

Other relics are held in Jerusalem by the Armenian Orthodox Church, the Greek Orthodox Church, and the Syriac Orthodox Church. There are three in St Peter’s Basilica, Rome.

In the absence of radiocarbon dating, their authenticity cannot be established.

St Helena, mother of emperor Constantine, is believed to have unearthed the True Cross in a cistern near Golgotha during preparations for building the original Church of the Holy Sepulchre over the site of the Crucifixion around 325.

Eusebius of Caesarea cites a letter written between 338 and 340 by Constantine to Bishop Macarius of Jerusalem saying that Helena had found “evidence of Christ’s holy Passion, which had lain hidden for so long”.

Helena is said to have divided the Cross into three pieces. She took one to Rome, left one in Jerusalem, and gave the third to her son to take to Constantinople, his new capital.

Fragments were soon circulating, as St Cyril of Jerusalem declared in 348 that the “whole earth is full of the relics of the Cross of Christ”.

The pilgrim Egeria wrote of venerating the piece in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre on Good Friday in 383.

In 638, as Muslim forces besieged Jerusalem, Patriarch Sophronius I divided the relic into 19 pieces and distributed them across the Middle East. Only four remained in Jerusalem when the Crusaders recaptured the city in 1099.

Titulus Christi in Rome (Reliquiosamente.com)

When the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople in 1204, the piece of the True Cross held there was carved up and slivers were given to churches, monasteries and palaces across Europe.

The devotion accorded these relics, often held in reliquaries of precious metals, no doubt encouraged the thriving trade in spurious items that took place at this time.

In Rome, Helena kept her part of the True Cross in her palace, the Palazzo Sessoriano, which she later converted into the Basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem — so called because she ordered soil from Jerusalem to be spread on the floor around the reliquary.

Three small pieces are still displayed there, along with other reputed relics of the Passion and a tablet called the Titulus Crucis, which was traditionally believed to have been part of the wooden notice placed by Pontius Pilate on the Cross, bearing the words “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews” in Hebrew, Latin and Greek. (John 19:19-20)

Radiocarbon dating tests on the Titulus were carried out by the Roma Tre University of Rome in 2002, giving a result of AD 980-1146, so it may be a copy of the lost original which pilgrims in the 4th and 6th centuries reported seeing in Jerusalem.

- Original negative of Italian photographer Secondo Pia in 1898 (Musée de l’Élysée, Lausanne)

- Pilgrims viewing the Shroud during an exposition in 2015 (Stefano Guidi / Shutterstock)

- Full-length negative of the front image on the Shroud (Wikipedia)

- Image on the Veil of Manoppello (ElfQrin / Wikipedia)

- Sudarium of Oviedo (Reinhard Dietrich / Wikipedia)

- Tunic of Argenteuil (Shroud.com)

- Reputedly the largest surviving piece of the True Cross, in Monastery of Saint Toribio De Liébana, Spain (Francisco J. Díez Martí / Wikipedia)

- Titulus Christi in Rome (Reliquiosamente.com)

References

Cruz, Joan Carroll: Relics (Our Sunday Visitor, 1984)

Górny, Grzegorz, and Rosikoń, Janusz: Witnesses to Mystery; Investigations into Christ’s Relics (Ignatius Press, 2019)

Pazos, Antón M. (ed): Relics, Shrines and Pilgrimages: Sanctity in Europe from Late Antiquity (Routledge, 2020)

The Basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem (official booklet)

Thiede, Carsten Peter, and D’Ancona, Matthew: The Quest for the True Cross (Phoenix, 2000)

Official websites

Shroud of Turin

Holy Face Sanctuary, Manoppello

Tunic of Argenteuil