West Bank

The Tombs of the Patriarchs in the West Bank city of Hebron is the burial place of three biblical couples — Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, and Jacob and Leah.

The second holiest site in Judaism (after the Western Wall in Jerusalem), it is also sacred to the other two Abrahamic faiths, Christianity and Islam.

It was the patriarch Abraham who bought the property when his wife Sarah died, around 2000 years before Christ was born. Genesis 23 tells how Abraham, then living nearby at Mamre, bought the land containing the Cave of Machpelah to use as a burial place. He paid Ephron the Hittite the full market price — 400 shekels of silver.

Today the site is the dominant feature of central Hebron, thanks to the fortress-like wall Herod the Great built around it in the same style of ashlar masonry that he used for the Temple Mount enclosure in Jerusalem.

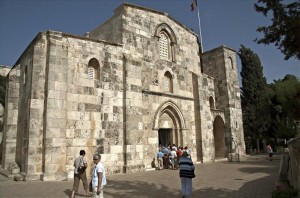

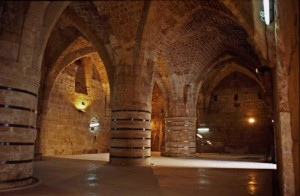

Herod left the interior open to the sky. The ruins of a Byzantine church built inside the wall around 570 were converted by Muslims into a mosque in the 7th century, rebuilt as a church by the Crusaders in the 12th century, then reconverted into a mosque by the sultan Saladin later in the same century.

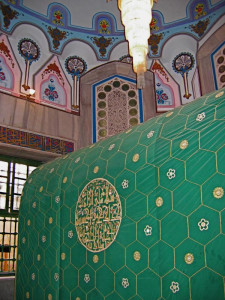

Most of the enclosure is now roofed. Inside, six cenotaphs covered with decorated tapestries represent the tombs of the patriarchs. The actual burial places of Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Rebekah, Jacob and Leah are in the cave beneath, to which access is not permitted.

Scene of God’s covenant with Abraham

Set in the Judean Mountains about 30 kilometres south of Jerusalem, Hebron stands 930 metres above sea level, making it the highest city in Israel and Palestine. It is also the largest city in the West Bank, with a population in 2007 of around 165,000 Palestinians and several hundred Jewish settlers, and is known for its glassware and pottery.

It was near Hebron that God made a covenant with Abraham, that he would be “the ancestor of a multitude of nations” (Genesis 17:4).

Abraham had pitched his tent “by the oaks of Mamre” (Genesis 13:18), 3 kilometres north of Hebron, at a site now in the possession of a small community of Russian Orthodox monks and nuns.

Here Abraham offered hospitality to three strangers, who told him his wife Sarah — then aged 90 — would have a son (Genesis 18:10-14).

When Moses led the Israelites out of Egypt, about 700 years after Abraham, the men he sent to spy out the land of Canaan returned from the Hebron area with a cluster of grapes so heavy that two men carried it on a pole between them — an image that is now the logo of the Israel Ministry of Tourism.

Later, King David ruled Judah from Hebron for seven and a half years before moving his capital to Jerusalem.

Emulating Abraham’s hospitality, early Muslim rulers of Hebron provided free bread and lentils each day to pilgrims and the poor.

Complex is in three sections

Herod’s mighty wall around the Tombs of the Patriarchs avoids the appearance of heaviness by clever visual deceptions. Each course of stone blocks is set back about 1.5 centimetres on the one below it, and the upper margin is wider than the others.

The corners of the edifice — called Haram al-Khalil (Shrine of the Friend [of God]) in Arabic — are oriented to the four points of the compass.

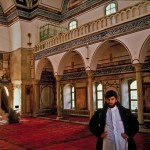

Inside, amid a confusing mix of minarets, domes, arches, columns and corridors of various styles and periods, the complex is divided into three main sections, each with the cenotaphs of a patriarch and his wife.

The main entrance, to the Muslim area, is up a long flight of steps beside the northwest Herodian wall, then east through the Djaouliyeh mosque (added outside the wall in the 14th century) and right to enter the enclosure.

Straight ahead, in the centre of the complex, are octagonal rooms containing the cenotaph of Sarah and, further on, the cenotaph of Abraham. Each of these domed monuments has a richly embroidered cover, light green for Sarah and darker green for Abraham.

In a corner just past Abraham’s room, a shrine displays a stone said to bear a footprint left by Adam as he left the Garden of Eden.

A wide door between these two cenotaphs leads to the Great Mosque, containing the cenotaphs of Isaac (on the right) and Rebekah. The vaulted ceiling, supporting pillars, capitals and upper stained-glass windows are from the Crusader church.

Ahead, on the southeastern wall, a marble-and-mosaic mihrab (prayer niche) faces Mecca. Beside it on the right is an exquisitely carved minbar (pulpit) of walnut wood. It was made (without nails) in 1091 for a mosque in Ashkelon and brought to Hebron a century later by Saladin after he burned that city.

Next to the pulpit, a stone canopy covers the sealed entrance to steps descending to the burial Cave of Machpelah.

Directly across the room, another canopy stands over a decorative grate covering a narrow shaft to the cave. Written prayers may be dropped down the shaft.

Entry to the Jewish area is via an external square building on the southwestern wall. This building houses a Muslim cenotaph of Joseph, one of Jacob’s sons (though Jews and Christians believe he was buried near Nablus).

Inside are synagogues and the cenotaphs of Jacob and Leah, each in an octagonal room. (Jacob’s beloved second wife, Rachel, is remembered at the Tomb of Rachel, on the Jerusalem-Hebron road north of Bethlehem).

Site and city are divided

Friction between Jews and Muslims at Hebron dates back to a 1929 riot in which Arab Muslims sacked the Jewish quarter and massacred 67 of its community.

More recently, in 1994 a Jewish settler entered the Tombs of the Patriarchs during dawn prayers and shot 29 Muslim worshippers (the mihrab still bears bullet marks).

Since then, Jews and Muslims have been restricted to their own areas of this divided site, except that each faith has 10 special days a year on which its members may enter all parts of the building. Pilgrims and tourists may enter both areas.

The city of Hebron is also divided into two zones. The larger part is governed by the Palestinian Authority. The remainder, including the town centre and market area, is occupied by Jewish settlers and under Israeli military control.

In 2019 Unesco named the old town of Hebron as a Palestinian world heritage site.

In Scripture

Abram settles by the oaks of Mamre at Hebron: Genesis 13:18

God makes a covenant with Abram and changes his name: Genesis 17:3-5

Three strangers pay a visit to Abraham: Genesis 18:1-16

Abraham haggles with God over the future of Sodom: Genesis 18:17-33

Sarah dies and Abraham buys the Cave of Machpelah: Genesis 23:1-20

Abraham dies and is buried with Sarah: Genesis 25:7-10

Joshua attacks Hebron and kills its inhabitants: Joshua 10:36-37

David is anointed king over Judah at Hebron: 2 Samuel 2:1-4, 11

Administered by: Islamic Waqf Foundation

Tel.: 972-2-222 8213/51

Open: Usually 7.30-11.30am, 1-2.30pm, 3.30-5pm; Muslim area closed on Fridays, Jewish area closed on Saturdays. Passport checks apply and it is wise to check the security situation before visiting (the Christian Information Centre in Jerusalem suggests telephoning 02-2227992).

- Tombs of the Patriarchs at Hebron (Seetheholyland.net)

- Tombs of the Patriarchs in central Hebron (Kourosh / Picasa)

- Herod’s stonework on Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- Old city market in Hebron (Marcin Monko)

- Cenotaph of Abraham in Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- Jewish sign outside Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- Inside Jewish synagogue in Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- Shoes outside Great Mosque in Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- Steps to enter Muslim area of Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- Jewish man praying at cenotaph of Abraham (Seetheholyland.net)

- Cenotaph of Sarah in Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- Street market in Hebron (Seetheholyland.net)

- Isaac and Ishmael bury their father Abraham in Cave of Machpelah, illustration from 1728 Figures de la Bible (Bizzell Bible Collection, University of Oklahoma Libraries)

- Checkpoint separating Israeli and Palestinian areas of Hebron (Itai / Wikimedia)

- Canopy over shaft to Cave of Machpelah (Seetheholyland.net)

- Entrance hall in Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- Cenotaph of Abraham in Tombs of the Patriarchs (Eric Stoltz)

- Guide who survived 1994 attack on worshippers at Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- Inside Djaouliyeh Mosque at Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- Cenotaphs of Rebekah and Isaac (Seetheholyland.net)

- Glassmarker at work in Hebron (Mrbrefast / Wikimedia)

- Israeli soldier guarding Jewish synagogue in Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox monastery at Mamre, where Abraham pitched his tent (CopperKettle / Wikimedia)

- Greek inscription dating from AD 327 near cenotaph of Abraham (Seetheholyland.net)

- Checkpoint at Jewish entrance to Tombs of the Patriarchs (PalFest)

- Minbar (pulpit) in Great Mosque in Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- Minaret on Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- View of cenotaph of Sarah from Jewish synagogue (A ntv / Wikimedia)

- Women’s section of synagogue in Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- View of cenotaph of Sarah from Jewish area in Tombs of the Patriarchs (Seetheholyland.net)

- Cenotaphs of Isaac (right) and Rebekah in Tombs of the Patriarchs (A ntv / Wikimedia)

- Mihrab (prayer niche) in Great Mosque at Tombs of the Patriarch (Seetheholyland.net)

- Bookholder in front of cenotaph of Sarah (Seetheholyland.net)

- Murals depicting Jewish settlement in Israeli-controlled area of Hebron (Itai / Wikimedia)

References

Beitzel, Barry J.: Biblica, The Bible Atlas: A Social and Historical Journey Through the Lands of the Bible (Global Book Publishing, 2007)

Brownrigg, Ronald: Come, See the Place: A Pilgrim Guide to the Holy Land (Hodder and Stoughton, 1985)

Chadwick, Jeffrey R.: “Discovering Hebron: the City of the Patriarchs Slowly Yields Its Secrets”, Biblical Archaeology Review, September/October 2005

Dyer, Charles H., and Hatteberg, Gregory A.: The New Christian Traveler’s Guide to the Holy Land (Moody, 2006)

Eber, Shirley, and O’Sullivan, Kevin: Israel and the Occupied Territories: The Rough Guide (Harrap-Columbus, 1989)

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Gonen, Rivka: Biblical Holy Places: An illustrated guide (Collier Macmillan, 1987)

Inman, Nick, and McDonald, Ferdie (eds): Jerusalem & the Holy Land (Eyewitness Travel Guide, Dorling Kindersley, 2007)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Prag, Kay: Israel & the Palestinian Territories: Blue Guide (A. & C. Black, 2002)

Shahin, Mariam, and Azar, George: Palestine: A guide (Chastleton Travel, 2005)