West Bank

In the Palestinian village of Sebastiya, Christians and Muslims alike honour a connection to John the Baptist at a location earlier known for the worship of Phoenician gods and a Roman emperor.

Sebastiya (with various spellings including Sebaste and Sebastia) is about 12 kilometres northwest of Nablus, to the east of the road to Jenin.

An early Christian tradition, from the first half of the 4th century, says John the Baptist’s disciples buried his body here after he was beheaded by Herod Antipas during the infamous banquet at which Salome’s dance enthralled the governor (Mark 6:21-29).

An Orthodox Christian tradition holds that Sebastiya was also the venue for the governor’s birthday banquet, though the historian Josephus says it was in Herod’s fortress at Machaerus, in modern-day Jordan.

Overlooking the present village of Sebastiya are the hilltop ruins of the royal city of Samaria. The city is mentioned more than 100 times in the Bible. Excavations have uncovered evidence of six successive cultures: Canaanite, Israelite, Hellenistic, Herodian, Roman and Byzantine.

The surrounding hill-country, its slopes etched by ancient terracing, has changed little in thousands of years.

When the early Christian community dispersed during the persecution that followed the martyrdom of St Stephen, the deacon Philip preached the Gospel in Samaria and was joined there by the apostles Peter and John.

City renamed by Herod the Great

Omri, the sixth king of the northern kingdom of Israel, built his capital on the rocky hill of Samaria in the ninth and eighth centuries before Christ.

His son Ahab fortified the city and, influenced by his wife Jezebel, a Phoenician princess, built temples to the Phoenician gods Baal and Astarte. Ahab’s evil deeds incurred the wrath of the prophet Elijah, who prophesied bloody deaths for both Ahab and Jezebel.

During its eventful history, Samaria was destroyed by Assyrians in 722 BC (ending the northern kingdom of Israel), captured by Alexander the Great in 331 BC, destroyed by the Maccabean King John Hyrcanus in 108 BC, and rebuilt by the Roman general Pompey in 63 BC.

Herod the Great expanded the city around 25 BC, renaming it Sebaste in honour of his patron Caesar Augustus (Sebaste is Greek for Augustus). Herod even built a temple dedicated to his patron, celebrated one of his many marriages in the city, and had two of his sons strangled there.

The pattern of destruction and rebuilding continued during the early Christian era. Sebaste became the seat of a bishop in the 4th century, was destroyed by an earthquake in the 6th century, flourished briefly under the Crusaders in the 12th century, then declined to the status of a village.

Pagans desecrated John’s tomb

Christian sources dating back to the 4th century place John the Baptist’s burial at Sebastiya, along with the remains of the prophets Elisha and Obadiah.

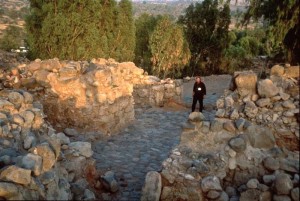

Crypt of the reputed tomb of John the Baptist (bottom centre) and other prophets (© ATS Pro Terra Sancta)

Around 390, while translating the Onomasticon (directory) of the holy places compiled by Eusebius, St Jerome describes Samaria/Sebaste as “where the remains of John the Baptist are guarded”.

By then, according to a contemporary account by the historian Rufinus of Aquileia around 362, pagans had desecrated the tomb during a persecution of Christians under emperor Julian the Apostate. The Baptist’s remains were burnt and the ashes dispersed, but passing monks saved some bones.

In the 6th century two urns covered in gold and silver were venerated by pilgrims. One was said to contain relics of John the Baptist, the other relics of Elisha.

Two churches were built during the Byzantine period. One was on the southern side of the Roman acropolis (on the site the Orthodox Church believes John was beheaded).

Greek Orthodox church, with apse at right and entrance to underground cave in centre (© Sebastiya Municipality)

The other church, a cathedral built over the Baptist’s reputed tomb, was just east of the old city walls and within the present village. Rebuilt by the Crusaders, it became the second biggest church in the Holy Land (after the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem).

But after the Islamic conquest of 1187 the cathedral was transformed into a mosque dedicated to the prophet Yahya, the Muslim name for John the Baptist. The mosque, rebuilt in 1892 within the ruins of the cathedral, is still in use.

Tomb is under cathedral ruins

Pilgrims still visit the tomb associated with John the Baptist and other prophets. Under a small domed building in the cathedral ruins, a narrow flight of 21 steps leads down to a tomb chamber with six burial niches set in the wall. Tradition places John the Baptist’s relics in the lower row, between those of Elisha and Obadiah.

The remains of the cathedral’s huge buttressed walls dominate Sebastiya’s public square.

In the extensive archaeological park at the top of the hill are remnants of Ahab’s palace, identified by the discovery of carved ivory that was mentioned in the Bible (1 Kings 22:39). The ivory pieces are displayed in the Rockefeller Museum, Jerusalem.

Also to be seen are the stone steps leading to Herod the Great’s temple of Augustus, an 800-metre colonnaded street, a Roman theatre and forum, and a city gate flanked by two watchtowers.

Interest in Sebastiya’s heritage and community — now entirely Muslim except for one Christian family — has been revived in the early 21st century by a project involving the Franciscan non-profit organisation ATS Pro Terra Sancta, funded by Italian aid.

In Scripture

King Omri moves his capital to Samaria: 1 Kings 16:23-24

Ahab erects an altar for Baal: 1 Kings 16:32

Ahab’s ivory house: 1 Kings 22:39

John the Baptist is beheaded: Mark 6:21-29

Philip preaches in Samaria: Acts 8:5

Peter and John go to Samaria: Acts 8:14

- Visitors and residents during Sebastiya’s first Heritage Day in 2010 (© ATS Pro Terra Sancta)

- Village of Sebastiya (Shuki / Wikipedia)

- Walls of Cathedral of St John the Baptist (© ATS Pro Terra Sancta)

- Greek Orthodox church, with apse at right and entrance to underground cave in centre (© Sebastiya Municipality)

- Cathedral of St John the Baptist, with tomb crypt under dome in centre (© ATS Pro Terra Sancta)

- Steps to where the Temple of Augustus stood (© ATS Pro Terra Sancta)

- Crypt of the reputed tomb of John the Baptist (bottom centre) and other prophets (© ATS Pro Terra Sancta)

- Inside the remains of the Greek Orthodox church (© Sebastiya Municipality)

- Reproduction of mosaic found at Sebastiya (© ATS Pro Terra Sancta)

- Stairway to tomb crypt beneath cathedral (© ATS Pro Terra Sancta)

- Sebastiya, with cathedral ruins in foreground (© Sebastiya Municipality)

- Hellenistic tower at Sebatiya (Shuki / Wikipedia)

- Olive trees along Sebastiya’s colonnaded street (© ATS Pro Terra Sancta)

- Entrance to tomb crypt, through Roman door at right (© ATS Pro Terra Sancta)

- Entrance to Greek Orthodox church (© Sebastiya Municipality)

- Pilgrims at Eucharist in church ruins (© Sebastiya Municipality)

- Cave under remains of Greek Orthodox church (© Sebastiya Municipality)

References

Blaiklock, E. M.: Eight Days in Israel (Ark Publishing, 1980)

Brisco, Thomas: Holman Bible Atlas (Broadman and Holman, 1998)

Dyer, Charles H., and Hatteberg, Gregory A.: The New Christian Traveler’s Guide to the Holy Land (Moody, 2006)

Eber, Shirley, and O’Sullivan, Kevin: Israel and the Occupied Territories: The Rough Guide (Harrap-Columbus, 1989)

Gonen, Rivka: Biblical Holy Places: An illustrated guide (Collier Macmillan, 1987)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Prag, Kay: Israel & the Palestinian Territories: Blue Guide (A. & C. Black, 2002)

Saltini, Tommaso (ed.): Sabastiya — The fruits of history and the memory of John the Baptist (ATS Pro Terra Sancta exhibition catalogue, 2011)

Walker, Peter: In the Steps of Jesus (Zondervan, 2006)

External links

Sebastia in the news (ATS Pro Terra Sancta)