Jerusalem

One of the most-visited graves in Jerusalem belongs to Oskar Schindler, the German factory-owner and Nazi Party member credited with saving the lives of 1098 Jews during the Second World War.

His grave in the Catholic cemetery on the southern slope of Mount Zion is visited by Jews, Christians and people of no religious faith.

A complex and conflicted man, Schindler was an unlikely candidate for heroism that involved risking his life to save others.

Born into a Catholic family in Moravia, he was unfaithful to his wife with a succession of mistresses. As a businessman he engaged in black-market dealings and bribery. An ethnic German but a Czech citizen, he worked as a counterintelligence agent for the Nazi armed forces (for which he was jailed by Czechoslovakia) and also collaborated in the German strategy for the invasion of Poland.

Ironically, Schindler’s less endearing character traits equipped him to ingratiate himself with Nazi officials for the sake of his Jewish employees.

At least nine lists were drawn up

After Germany occupied Poland in 1939, the opportunistic Schindler moved to the Polish city of Krakow and took over a Jewish-owned enamelware factory.

Because the factory was close to the Jewish ghetto he was able to witness the brutal German oppression at firsthand. “And then a thinking man, who had overcome his inner cowardice, simply had to help. There was no other choice,” he said after the war.

Schindler built up his workforce with Jewish forced labourers from the Plaszow labour camp, bribing officials to ensure their wellbeing. He and his wife Emilie especially cared for those who were old or weak.

In 1944, when the inmates of Plaszow were destined for deportation to death camps such as Auschwitz, Schindler obtained approval (after paying the necessary bribes) to move his factory to Brünnlitz in Czechoslovakia, on the pretext of making armaments.

The names of the workers chosen to move to the new factory formed the “list” made famous in Thomas Keneally’s 1982 Booker Prize-winning novel Schindler’s Ark and Steven Spielberg’s 1993 Academy Award-winning movie Schindler’s List.

In fact, according to Schindler’s definitive biographer David M. Crowe, at least nine lists, constantly changing, were drawn up in late 1944 and 1945, and they were drawn up by other people — although Schindler had given guidelines as to who he wanted included. However, without Schindler’s efforts there would have been no Jewish workers to be listed.

Declared Righteous Among the Nations

By the time the war ended, Schindler’s considerable wealth had been spent on bribes and black-market supplies for his workers and he was reduced to receiving handouts from Jewish organisations.

In 1949 he emigrated to Argentina with his long-suffering wife, his current mistress and some Jewish friends. After a farming venture failed he returned alone to Germany and established a cement factory that went bankrupt.

In the 1960s he began annual visits to Israel, where he was feted as a hero, but he was in poverty when he died in 1974, aged 66, in Hildesheim, Germany. It was his own wish to be buried in Jerusalem.

Emilie Schindler remained in Argentina, living on a pension. She died in 2001 during a visit to Berlin, aged 94.

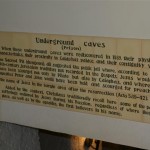

In 1962 a tree was planted in Oskar Schindler’s honour in the Avenue of the Righteous at the Yad Vashem Holocaust museum in Jerusalem. But it was not until 1993 that both Oskar and Emilie were officially recognised by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations.

Visitors leave stones on grave

Schindler’s grave in the Mount Zion Catholic Cemetery — not the Protestant Cemetery further west, as some guidebooks have it — is within easy walking distance of the Old City’s Zion Gate.

Walk out Zion Gate towards the bus parking lot. Take the road on the left until it joins a major road called Ma’aleh Hashalom. Follow this road down the slope of Mount Zion until you come to a high stone wall on the left with a wrought-iron gate. High on the gate is small sign reading “To Oskar Schindler’s Grave”.

For times when the cemetery is closed, the Muslim custodian’s phone number is painted roughly on the gate.

The cemetery is on two levels, with circular steps leading down to the lower level where Schindler is buried. Many of the graves are of Franciscan monks and nuns. Others, as their Arabic inscriptions indicate, belong to Arab Catholic families whose family trees date back hundreds of years.

At the edge of the top level stands a large cross. Facing the cross, look down on the lower level at about 2 o’clock. The flat slab of Schindler’s last resting place stands out from the other graves because of the stones left on it by visitors — a Jewish custom that is also followed by many others who come to pay their respects.

The stones often partly cover the inscriptions, which read (in Hebrew) “Righteous Among the Nations” and (in German) “The Unforgettable Lifesaver of 1200 Persecuted Jews”.

Open: Usually 8-12am (closed Sunday)

Tel.: 0525-388342

- Oskar Schindler in 1947 (Freeinfosociety.com)

- Oskar Schindler’s grave (Seetheholyland.net)

- Part of Schindler’s Krakow factory in 2009 (Jongleur100 / Wikimedia)

- Photos in Krakow factory of people saved by Schindler (Zorro2212 / Wikimedia)

- Entrance to Mount Zion Catholic Cemetery (Yoninah / Wikimedia)

- Memorial plaque near central railway station in Frankfurt (Frank Behnsen / Wikimedia)

- Franciscan friar placing flowers in cemetery (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

- Looking down to lower level of cemetery, with Schindler’s grave in centre (Seetheholyland.net)

- Visitors at Mount Zion Catholic Cemetery (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

- Schindler’s Brünnlitz factory in 2004 (Miaow Miaow / Wikimedia)

- Products made in Schindler’s Krakow factory (Zorro2212 / Wikimedia)

- Emilie and Oskar Schindler in 1946 (Wikimedia)

- Memorial plaque in Hildesheim (Torbenbrinker / Wikimedia)

- Visitors at the Krakow factory (Ian Rutherford)

- Marker plaque at Yad Vashem (Ricardo Tulio Gandelman)

References

Burkeman, Oliver, and Aris, Ben: “Biographer Takes Shine off Spielberg’s Schindler”, The Guardian, November 25, 2004

Crowe, David M.: Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account of his Life, Wartime Activities, and the True Story Behind the List (Westview Press, 2004)

Keneally, Thomas: Schindler’s Ark (Hodder and Stoughton, 1982)

Rubenstein, Danny: “A Sign Points to the Grave”, Haaretz, July 19, 2007

Smith, Dinitia: “A Scholar’s Book Adds Layers of Comploexity to the Schindler Legend”, The New York Times, November 24, 2004

External links

Oscar Schindler (Louis Bülow)

Oskar Schindler (Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team)

Oskar Schindler (Encyclopedia of World Biography)

Oskar Schindler (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

The Real Oskar Schindler (Herbert Steinhouse)