West Bank

Though the Inn of the Good Samaritan existed only in a parable, a real-life site was proposed in the early Christian centuries to edify the faith of pilgrims.

The location, beside the road going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, fitted Jesus’ parable about the man who “fell into the hands of robbers, who stripped him, beat him, and went away, leaving him half dead” (Luke 10:25-37).

In the 6th century a Byzantine monastery with pilgrim accommodation was erected on the site of what was probably some sort of travellers’ hostel well before the time of Jesus. Later the Crusaders established a fortress on a nearby hill to protect pilgrims against robbers.

The remains of the monastery, about 18 kilometres from Jerusalem, became an Ottoman caravanserai and then served as a police post during the 20th century.

In 2009 Israel built a mosaic museum on the site — a matter of controversy since the area is in the West Bank and under Israeli military and civil control.

The remains of the monastery church were reconstructed as a space for worship, with an altar but no cross or other visible Christian symbol.

Road was notorious for robbers

Modern road from Jerusalem down to Jericho in vicinity of Inn of the Good Samaritan (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

Jesus would have been familiar with the road. He would often have walked it on the final stretch of the way from Galilee to Jerusalem along the Jordan Valley.

It was here that the Mount of Olives and Mount Scopus gave travellers from Jericho their first glimpse of Jerusalem.

The rocky desert terrain around where the Inn of the Good Samaritan now stands was notorious for robbers. The local name for the area — Ma‘ale Adummim (“ascent of the red rocks”) — came from patches of limestone tinted red by iron oxide, but also suggested bloody raids by bandits.

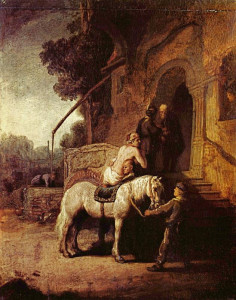

The Good Samaritan, depicted on arrival at the inn, by Rembrandt van Rijn, 1630 (Wallace Collection, London)

In the parable, a priest and a Levite saw the man who had been robbed but “passed by on the other side”. But a travelling Samaritan was “moved with pity”, tended the man’s wounds, took him to an inn and paid for his care.

The 12,000 Jericho-based priests and Levites used the road whenever they were rostered to serve in the Temple. But a traveller from Samaria would have been regarded as an alien in Judea.

So Jesus chose an unlikely hero — one whose people were at enmity with the Jews — to demonstrate that loving one’s neighbour requires expanding the definition of neighbour to include even an enemy.

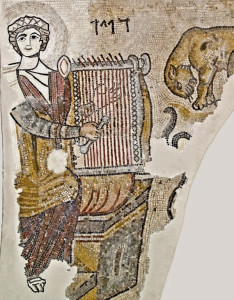

Mosaics come from synagogues and churches

The museum is one of the largest in the world devoted to mosaics. Displays both indoors and outdoors include mosaics from Jewish and Samaritan synagogues, as well as from Christian churches, in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza.

Some of the mosaics date back to the 4th century AD. Many have been removed from archaeological sites, while others have been partly or wholly reconstructed.

The designs include rich geometric patterns, birds and flowers. Some have Greek, Hebrew or Samaritan inscriptions.

Displays also include findings from a nine-year archaeological excavation in the area. Among them are pottery, coins and stone coffins from the 1st century BC, and a carved pulpit, a case for holy relics and a dining table from the Byzantine era.

In Scripture:

Parable of the Good Samaritan: Luke 10:25-37

Administered by: Israel Nature and Parks Authority

Tel.: 972-2-6338230

Open: Sunday-Thursday and Saturday, 8am-4pm; Friday and holiday eves, 8am-3pm; eves of Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur and Passover, 8am-1pm.

- King David playing harp, mosaic at Museum of the Good Samaritan (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Archaeological site and (at rear) worship area (© Whitecapwendy)

- Modern road from Jerusalem down to Jericho in vicinity of Inn of the Good Samaritan (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

- The Good Samaritan, depicted on arrival at the inn, by Rembrandt van Rijn, 1630 (Wallace Collection, London)

- Entrance to Museum of the Good Samaritan (Josh Evnin)

- Byzantine church pulpit in Museum of the Good Samaritan (Yair Talmor)

- Museum of the Good Samaritan beside Jericho road (Bukvoed)

- View towards Jericho from Mt Scopus, Jerusalem (David Q. Hall)

- Mosaic at Museum of the Good Samaritan (Yair Talmor)

- Museum of the Good Samaritan (Yair Talmor)

- Museum of the Good Samaritan (© Whitecapwendy)

- Mosaic at Museum of the Good Samaritan (Yair Talmor)

- Stone window from a Byzantine church, at Museum of the Good Samaritan (Yair Talmor)

- Stone window from a Byzantine church, at Museum of the Good Samaritan (Yair Talmor)

- Mosaic at Museum of the Good Samaritan (Yair Talmor)

- Chancel posts from a Byzantine church, at Museum of the Good Samaritan (Yair Talmor)

References

Gonen, Rivka: Biblical Holy Places: An illustrated guide (Collier Macmillan, 1987)

Lefkovits, Etgar: “Mosaic museum opens in the W. Bank”, Jerusalem Post, June 7, 2009

Mackowski, Richard M.: Jerusalem: City of Jesus (William B. Eerdmans, 1980)

Prag, Kay: Jerusalem: Blue Guide (A. & C. Black, 1989)

Wareham, Norman, and Gill, Jill: Every Pilgrim’s Guide to the Holy Land (Canterbury Press, 1996)