Jerusalem

Mount Zion, the highest point in ancient Jerusalem, is the broad hill south of the Old City’s Armenian Quarter.

Also called Sion, its name in Old Testament times became projected into a metaphoric symbol for the whole city and the Promised Land.

Several important events in the early Christian Church are likely to have taken place on Mount Zion:

• The Last Supper of Jesus and his disciples, and the coming of the Holy Spirit on the disciples, both believed to have been on the site of the Cenacle;

• The appearance of Jesus before the high priest Caiaphas, believed to have been at the site of the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu;

• The “falling asleep” of the Virgin Mary, believed to have occurred at the site of the Church of the Dormition.

• The Council of Jerusalem, around AD 50, in which the early Church debated the status of converted gentiles (Acts 15:1-29), perhaps also on the site of the Cenacle.

The mountain that moved

In the Old Testament period, Zion was the eastern fortress that King David captured from the Jebusites and named the City of David (2 Samuel 5:6-9).

A psalmist described Mount Zion as God’s “holy mountain, beautiful in elevation . . . the joy of all the earth” (Psalm 48).

And again, “Those who trust in the Lord are like Mount Zion, which cannot be moved, but abides forever” (Psalm 125).

Ironically, by the time this psalm was composed, the name of Mount Zion had already moved from its original location at the Jebusite fortress — and would move again.

First, perhaps at the time Solomon built his Temple, the Temple Mount came to be called Mount Zion. Then in the first century AD, following the Roman destruction of Jerusalem, the name was transferred to its present location across the Tyropoeon Valley.

Early Christians built synagogue-church

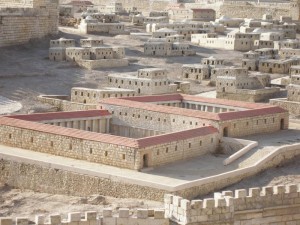

In the time of Christ, Mount Zion was a wealthy neighbourhood, densely populated and enclosed within the city walls.

There was also a community of Essenes, a group who lived a strict interpretation of Mosaic Law. They are better known for their community at Qumran, where the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered.

The first-century Christians met on Mount Zion, where they built a Judaeo-Christian synagogue-church that became known as the Church of the Apostles.

Over the centuries a succession of churches were built on the site and later destroyed. These included the great Byzantine basilica Church of Hagia Sion (Holy Zion), known as the “Mother of all Churches” — which covered the entire area now occupied by the Church of the Dormition, the Cenacle and the Tomb of David.

David’s tomb is empty

The Old Testament (1 Kings: 2:10) records that King David was buried in the city of David, which was on the original Mount Zion.

King David’s Tomb after extensive renovations were completed in 2013 (Seetheholyland.net)

Because the name of Mount Zion had moved to its present location, as described above, Christian pilgrims in the 10th century developed a belief that David’s burial place was there too.

It was actually the Christian Crusaders who built the present memorial on Mount Zion called the Tomb of King David. However, three of the walls of the room where its empty cenotaph stands are apparently from the synagogue-church used by the first-century Judaeo-Christians.

Gradually this memorial came to be accepted as David’s tomb, first by the Jews and later also by Muslims.

Architects beheaded for excluding Mount Zion

The respect with which Muslims held King David is illustrated by a legend relating to the reconstruction of Jerusalem’s walls by the Turkish conqueror Sulieman the Magnificent in the mid-16th century.

As the story goes, the sultan was furious when he discovered that the new walls did not encompass Mount Zion, leaving the Tomb of David unprotected.

He summoned the two architects responsible for the project and ordered that they be beheaded. Two graves in the inner courtyard of Jaffa Gate are said to be those of the architects.

Another place of interest on Mount Zion is the grave of Oskar Schindler, a German industrialist who saved nearly 1200 Jews in the Holocaust and has been declared a Righteous Gentile. The grave is in the Catholic cemetery near Zion Gate.

Related sites

Church of St Peter in Gallicantu

In Scripture:

The Last Supper: Matthew 26:17-30; Mark 14:12-25; Luke 22:7-23; John 13:1—17:26

The coming of the Holy Spirit: Acts 2:1-4

Jesus appears before Caiaphas: Matthew 26:57-68; Mark 14:53-65; Luke 22:66-71; John 18:12-14, 19:24

The first Church Council of Jerusalem: Acts 15:1-29

- Building containing the Cenacle and the Tomb of King David (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

- Tomb of King David on Mount Zion (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Cenacle on Mount Zion (Seetheholyland.net)

- Mount Zion, crowned by the Dormition Abbey (© Deror Avi)

- Dormition Abbey atop Mount Zion (Seetheholyland.net)

- Steps to House of Caiphas on Mount Zion (Seetheholyland.net)

- Grave of Oskar Schindler in Catholic cemetery on Mount Zion (Seetheholyland.net)

- Church of the Dormition on Mount Zion (Seetheholyland.net)

- Hagia Sion sign at Dormition Abbey (Glenn Johnson / Wikimedia)

- Old City from Mt Zion (Seetheholyland.net)

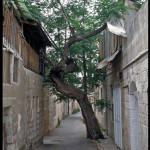

- Walled path on Mount Zion (© Deror Avi)

- Mount Zion and, at right, Old City walls (© Deror Avi)

- Church of St Peter in Gallicantu on Mount Zion (Seetheholyland.net)

- Hinnom Valley looking north-east to Mount Zion and Old City (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Church of the Dormition on Mount Zion (Seetheholyland.net)

References

Anonymous: “Christian Mount Sion”, Holy Land, spring 2003

Gonen, Rivka: Biblical Holy Places: An illustrated guide (Collier Macmillan, 1987)

Inman, Nick, and McDonald, Ferdie (eds): Jerusalem & the Holy Land (Eyewitness Travel Guide, Dorling Kindersley, 2007)

Mackowski, Richard M.: Jerusalem: City of Jesus (William B. Eerdmans, 1980)

Metzger, Bruce M., and Coogan, Michael D.: The Oxford Companion to the Bible (Oxford University Press, 1993)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Pixner, Bargil: “Church of Apostles found on Mt Zion” (Biblical Archaeological Review, May/June 1990)

Wareham, Norman, and Gill, Jill: Every Pilgrim’s Guide to the Holy Land (Canterbury Press, 1996)

External links