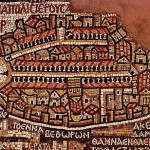

Jerusalem

The Temple Mount, a massive masonry platform occupying the south-east corner of Jerusalem’s Old City, has hallowed connections for Jews, Christians and Muslims.

All three of these Abrahamic faiths regard it as the location of Mount Moriah, where Abraham prepared to offer his son Isaac (or Ishmael in the Muslim tradition) to God.

• For Jews, it is where their Temple once stood, housing the Ark of the Covenant. Now, for fear of stepping on the site of the Holy of Holies, orthodox Jews do not ascend to the Temple Mount. Instead, they worship at its Western Wall while they hope for a rebuilt Temple to rise with the coming of their long-awaited Messiah.

• For Christians, the Temple featured prominently in the life of Jesus. Here he was presented as a baby. Here as a 12-year-old he was found among the teachers after the annual Passover pilgrimage.

Here Jesus prayed and taught. Here he overturned money-changers’ tables and foretold the destruction of the Temple: “Not one stone will be left here upon another; all will be thrown down” (Mark 13:2). And here the earliest Judaeo-Christians met.

• For Muslims, the Temple Mount is al-Haram al-Sharif (the Noble Sanctuary). It is Islam’s third holiest site, after Mecca and Medina, and the whole area is regarded as a mosque.

Muslims believe their gold-roofed Dome of the Rock — an iconic symbol of Jerusalem — covers the rock from which Muhammad visited heaven during his Night Journey in the 7th century.

Solomon built First Temple

Israel’s King Solomon built the first Temple around 950 BC on the traditional site of Mount Moriah. His father, King David, had bought a Jebusite threshing floor on the windy hilltop where Abraham had prepared to sacrifice Isaac and “built there an altar to the Lord” (2 Samuel 24:25) some 40 years earlier.

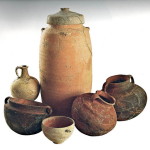

Solomon’s lavish Temple, built of stone and timber with an exterior of white marble and a gold-plated façade, was to provide a fitting resting place for the Ark of the Covenant, containing the stone tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments.

Its altar, the central place where Jews offered sacrifices to Yahweh, was probably close to the sites of Abraham’s and David’s altars.

Solomon’s Temple stood for about 360 years until invading Babylonians destroyed it and took most of the Jews into exile. The Mishnah says the Ark of the Covenant was hidden in an underground chamber. What became of it is unknown, though the second book of Maccabees says the prophet Jeremiah hid it in a cave on Mount Nebo (2:4-6).

Fifty years later the Jews were allowed to return from Babylon. They rebuilt the Temple, completing it in 515 BC.

Herod built second Temple

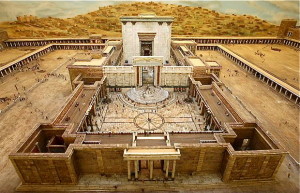

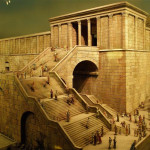

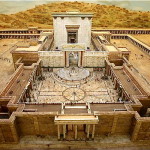

The Temple Jesus knew was rebuilt by Herod the Great in a project he began around 20 BC. Although the Temple had already been rebuilt once, Herod’s Temple is still known in Jewish tradition as the Second Temple.

Herod began his grandiose project by extending the Temple Mount on the north, south and west to create a vast platform bordered by a retaining wall of huge limestone blocks.

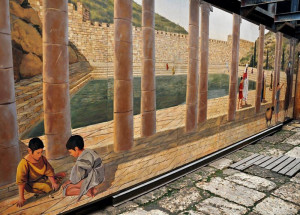

Court of the Women in a model of Herod’s Temple by English pensioner Alec Garrard (© Geoff Robinson)

These blocks, some weighing more than 100 tons, were cut from quarries at a higher level, just north of the Temple Mount, and put in place with pulleys and cranes.

The expansion — to today’s 14 hectares, nearly twice the previous area — involved burying several structures, including Solomon’s palace.

Of the Temple itself, the historian Josephus said “it appeared from a distance like a snow-clad mountain; for all that was not overlaid with gold was of purest white”.

Surrounding the Temple were four courts: The Court of the Priests (containing the altar of sacrifice); the Court of Israel (for men only); the Court of the Women; and, on a lower level, the Court of the Gentiles. Notices warned Gentiles not to enter the higher courts on the pain of death.

Along each edge of the Temple Mount was a covered and columned gallery called a portico. Solomon’s Portico, on the east, was probably where Mary and Joseph found their son among the teachers of the Law. The Royal Stoa, on the south, was a place of public business and trade.

Romans destroyed Temple

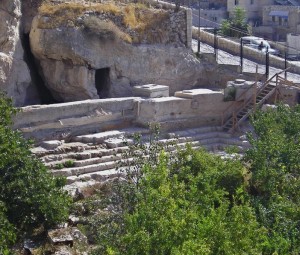

Masonry blocks thrown by Roman soldiers on to street below when they destroyed the Temple (Freestockphotos.com)

Herod’s Temple was totally destroyed when the Roman army under the emperor Titus took Jerusalem in AD 70, ending the First Jewish Revolt. As Jesus had prophesied, not one stone was left upon another.

The emperor Hadrian in AD 130 converted Jerusalem into a Roman colony, called Aelia Capitolina, which Jews were forbidden to enter. Hadrian placed statues of himself on the Temple Mount.

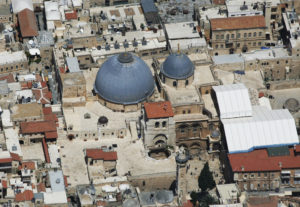

After the Roman Empire adopted Christianity in the 4th century, the emperor Constantine’s mother, St Helena, is believed to have built a small church on the Temple Mount. Otherwise the area was ignored — it was actually used for a rubbish dump — while Christians focused on the new Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Arab Muslims conquered Jerusalem in the 7th century and converted the Temple Mount into an Islamic sanctuary. They cleared the rubbish and erected the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque.

When Crusaders captured Jerusalem in 1099 they Christianised these Muslim structures and gave them misleading names. The Dome of the Rock became a church called the Templum Domini (Temple of the Lord); the Al-Aqsa Mosque became the palace of the King of Jerusalem, then the headquarters of the Knights Templar, under the name of the Templum Salomonis (Temple of Solomon).

Muslims under the sultan Saladin reconquered Jerusalem less than a century later, restoring the Noble Sanctuary to its former Islamic status. Even after Israeli forces captured the Temple Mount from Jordan in the 1967 Six Day War, Israel left its management in the hands of an Islamic foundation (called the Waqf), which has undertaken controversial digs and earthworks.

Judgement scales and Messiah’s entry

Arches where Muslim tradition says scales to weigh souls will be hung at Last Judgement (Seetheholyland.net)

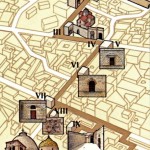

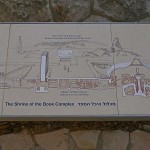

Today’s Temple Mount is a spacious plaza of minarets, domed pavilions, fountains, date palms and cypress trees. It occupies about one-sixth of the Old City.

Eight stairways ascend to the platform of the Dome of the Rock, each culminating in a set of slender arches where Islamic tradition says scales to weigh souls will be hung at the Last Judgement.

In the southwest corner of the Temple Mount, near the Al-Aqsa Mosque, the Islamic Museum displays ceramics, gifts to the sanctuary and architectural items removed during restorations.

The walls of the Temple Mount platform originally contained several gateways, with stairs or ramps leading to and from the city. All are now blocked, though the outlines of some are still visible.

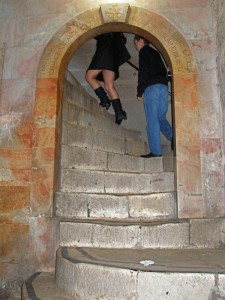

In the eastern wall were the Golden Gate, through which Jews expect their Messiah will enter Jerusalem, and the gate from which the scapegoat was driven into the wilderness on the Day of Atonement. Most pilgrims entered the Temple Mount at the southeast corner through the Double Gate, whose steps have been reconstructed.

To the right of the Western Wall plaza can be seen the stub of Robinson’s Arch (named after a 19th-century archaeologist), which supported a monumental staircase from the street to the Temple Mount.

Over the centuries the deep valley that ran beside the Western Wall in the time of Jesus became filled with rubble. Today’s wall stands 19 metres high, but a further 13 metres of Herod’s blockwork lie hidden beneath ground level.

Sites in the Temple Mount area:

In Scripture:

Abraham prepares to sacrifice Isaac: Genesis 22:1-19

David buys the threshing floor: 2 Samuel 24:18-25

Solomon builds the First Temple: 1 Kings 5-6

Jeremiah hides the Ark of the Covenant: 2 Maccabees 4-6

Jesus is presented in the Temple: Luke 2:22-38

Jesus is found among the teachers in the Temple: Luke 2:41-51

Jesus cleanses the Temple: John 2:14-16

Jesus prophesies the destruction of the Temple: Matthew 24:1-2

Administered by: Islamic Waqf Foundation

Open: Non-Muslims are permitted to enter the Temple Mount through the Bab Al-Maghariba (Moors’ Gate), reached through a covered walkway next to the Western Wall plaza, during restricted hours. These are usually 7.30-11am and 1.30-2.30pm (closed Fridays and on religious holidays), but can change. Access is not allowed during times of Muslim prayer nor at times of tension between Arabs and Jews. Modest dress is required. Non-Muslims are not normally allowed into the Dome of the Rock or the Al-Aqsa Mosque. Non-Muslim prayer on the Temple Mount is not permitted.

- Warning to Jews at entrance to Temple Mount (Chad Rosenthal)

- Golden menorah as used in the Temple (Seetheholyland.net)

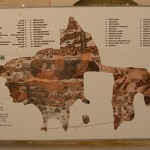

- Model of Herod’s Temple at Israel Museum (James Emery)

- Model in Tower of David Museum showing an entrance to the Temple (Seetheholyland.net)

- Ornate Bab Al-Qattanin Gate (Seetheholyland.net)

- Temple Mount model in Schmidt’s College, Jerusalem (© Deror Avi)

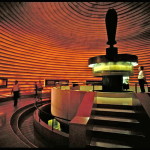

- Inside Royal Stoa of Alec Garrard’s Temple model (© Geoff Robinson)

- Southwest corner of Temple Mount showing masonry from four historical periods (Chris Yunker)

- Dome of the Chain in front of Dome of the Rock (Seetheholyland.net)

- Capitals and fragments of columns displayed on Temple Mount (Seetheholyland.net)

- Arch of Titus in Rome showing menorah and other Temple treasures being carried in triumphal procession (Anthony Majanlahti / Wikimedia)

- Interior of Dome of the Chain (Zeev Barkan)

- Ornately inscribed Fountain of Sultan Qaytbay (Seetheholyland.net)

- Arched entrances along the western edge of the Temple Mount (Seetheholyland.net)

- Arabic sundial on Temple Mount arches (Chad Rosenthal)

- Ablutions fountain in front of Al-Aqsa Mosque (Chris Yunker)

- View across Temple Mount, with Dome of the Chain at left (Chris Yunker)

- Twin portals of Golden Gate on Temple Mount (Caleb Zahnd)

- Arches where Muslim tradition says scales to weigh souls will be hung at Last Judgement (Seetheholyland.net)

- Exterior view of Golden Gate in wall of Temple Mount (Ian W. Scott)

- Al-Aqsa Mosque (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Remains of Robinson’s Arch, which supported a stairway to the Temple (Seetheholyland.net)

- Masonry blocks thrown by Roman soldiers on to street below when they destroyed the Temple (Freestockphotos.com)

- Rock of Mount Moriah as it was in 1910 (Robert Smythe Hichens / Wikimedia)

- Model of Herod’s Temple by English pensioner Alec Garrard (© Geoff Robinson)

- Temple Mount visitors in front of Dome of the Rock (Seetheholyland.net)

- Walled platform of Jerusalem’s Temple Mount (Yonderboy / Wikimedia)

- Court of the Women in a model of Herod’s Temple by English pensioner Alec Garrard (© Geoff Robinson)

- Olive trees on the Temple Mount (Seetheholyland.net)

References

Bahat, Dan: “Jerusalem Down Under: Tunneling Along Herod’s Temple Mount Wall” (Biblical Archaeological Review, November/December 1995)

Baldwin, David: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Companion (Catholic Truth Society, 2007)

Bourbon, Fabio, and Lavagno, Enrico: The Holy Land Archaeological Guide to Israel, Sinai and Jordan (White Star, 2009)

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Garrard, Alec: The Splendor of the Temple (Angus Hudson, 2000)

Jacobson, David: “Sacred Geometry: Unlocking the Secret of the Temple Mount” (Biblical Archaeological Review, July/August and September/October 1999)

Kochav, Sarah: Israel: A Journey Through the Art and History of the Holy Land (Steimatzky, 2008)

McCormick, James R.: Jerusalem and the Holy Land: The first ecumenical pilgrim’s guide (Rhodes & Eaton, 1997)

Mackowski, Richard M.: Jerusalem: City of Jesus (William B. Eerdmans, 1980)

Metzger, Bruce M., and Coogan, Michael D.: The Oxford Companion to the Bible (Oxford University Press, 1993)

Meyer, Gabriel: “The Temple and the Lord” (Holy Land Review, winter 2010)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Notley, R. Steven: Jerusalem: City of the Great King (Carta Jerusalem, 2015)

Prag, Kay: Jerusalem: Blue Guide (A. & C. Black, 1989)

Ritmeyer, Leen: “Locating the Original Temple Mount” (Biblical Archaeological Review, March/April 1992)

Walker, Peter: In the Steps of Jesus (Zondervan, 2006)

Wareham, Norman, and Gill, Jill: Every Pilgrim’s Guide to the Holy Land (Canterbury Press, 1996)

Woodfin, Warren T.: “The Holiest Ground in the World” (Biblical Archaeological Review, September/October 2000)

External links

The Noble Sanctuary

Temple Mount (Wikipedia)