Jerusalem

One of the most striking churches in Jerusalem commemorates the apostle Peter’s triple denial of his Master, his immediate repentance and his reconciliation with Christ after the Resurrection.

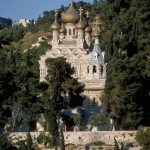

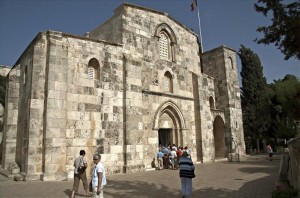

Built on an almost sheer hillside, the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu stands on the eastern slope of Mount Zion.

On its roof rises a golden rooster atop a black cross — recalling Christ’s prophesy that Peter would deny him three times “before the cock crows”. Galli-cantu means cockcrow in Latin.

Peter’s denial of Christ is recorded in all four Gospels (most succinctly in Matthew 26:69-75). Three of the Gospels also record his bitter tears of remorse.

The scene of Peter’s disgrace was the courtyard of the high priest Caiaphas. The Assumptionist congregation, which built St Peter in Gallicantu over the ruins of a Byzantine basilica, believes it stands on the site of the high priest’s house.

Under the church is a dungeon thought to be the cell where Jesus was detained for the night following his arrest.

Blend of contemporary and ancient art

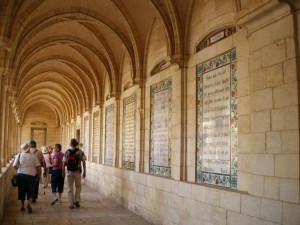

The Church of St Peter in Gallicantu is built on four different levels — upper church, middle church, guardroom and dungeon. Its design and art are a colourful blend of contemporary and ancient works.

In the courtyard a statue depicts the denial, including the rooster, the woman who questioned Peter, and a Roman soldier.

Inside, on the right, are two Byzantine-era mosaics. Uncovered during excavation, they were most likely part of the floor of the fifth-century Byzantine church.

The ceiling is a striking feature. It is dominated by a huge cross-shaped window designed in a radiant variety of colours.

Three large mosaics cover the back wall and two side walls. Facing the entrance is a bound Jesus being questioned in the house of Caiaphas; on the right, Jesus and the disciples are shown at the Last Supper; on the left, Peter is depicted in ancient papal dress as the first pope.

Downstairs, in the middle church, icons above the altars depict St Peter’s denial, his repentance and his reconciliation with his Master on the shore of the Sea of Galilee after the Resurrection.

Many of the inscriptions in the church are in French, since the Assumptionists are a French religious order.

Guardroom and prisoner’s cell

The lower levels of the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu contain what are believed to have been a guardroom and a prisoner’s cell, both hewn out of bedrock.

• The guardroom contains wall fixtures to attach prisoners’ chains. Holes in the stone pillars would have been used to fasten a prisoner’s hands and feet when he was flogged. Bowls carved in the floor are believed to have contained salt and vinegar, either to aggravate the pain or to disinfect the wounds.

Jesus, of course, was not flogged by the Jews but by the Romans. But some of his disciples, probably including Peter, were flogged by order of the Jewish council after the Resurrection for teaching in the name of Jesus in the Temple (Acts 5:40).

• The prisoner’s cell offers a sobering insight into where Christ might have spent the night before he was crucified. It has become known as “Christ’s Prison”.

The only access to the bottle-necked cell was through a shaft from above, so the prisoner would have been lowered and raised by means of a rope harness. A mosaic depicting Jesus in such a harness is outside on the south wall of the church.

A small window from the guardroom served as a peephole for a guard standing on a stone block.

Disagreement over house of Caiaphas

Though pilgrims’ reports back as far as AD 333 attest to this place being the site of the house of Caiaphas, archaeologists are divided.

Some favour an alternative site for the high priest’s house at the Armenian Orthodox Church of the House of Caiaphas on the summit of Mount Zion, adjacent to the Dormition Abbey.

Jerome Murphy-O’Connor considers it “much more likely that the house of the high priest was at the top of the hill”.

Bargil Pixner, a former prior of the Dormition Abbey, disagrees, saying “this late and astonishing theory originated at the time of the Crusaders and is quite improbable”.

Excavations at St Peter in Gallicantu have revealed a water cistern, corn mill, storage chambers and servants’ quarters.

Artefacts discovered include a complete set of weights and measures for liquids and solids as used by the priests in the Temple, and a door lintel with the word “Korban” (sacrificial offering) inscribed in Hebrew.

Steps that Jesus trod

Beside the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu, excavations have brought to light a stepped street which in ancient times would have descended from Mount Zion to the Kidron Valley.

These stone steps were certainly in use at the time of Christ. On the evening of his arrest, he probably descended them with his disciples on their way from the Last Supper to Gethsemane.

And, even if the House of Caiphas was situated further up Mount Zion than the present church, it would have been by this route that Jesus was brought under guard to the high priest’s house.

The Church of St Peter in Gallicantu illustrates the tumultuous history of religious sites in the Holy Land: A major church built here in 457 was damaged in 529 during the Samaritan Revolt and destroyed in 614 by the Persians. It was rebuilt around 628 and destroyed in 1009 by the mad Caliph Hakim. Rebuilt around 1100 by the Crusaders, it was destroyed in 1219 by the Turks. Then a chapel was built, but it was destroyed around 1300. The present church was completed in 1932.

In Scripture:

Peter denies Jesus: Matthew 26:69-75

Administered by: Augustinians of the Assumption

Tel.: 972-2-6731739

Open: 8.30am-5pm (closed Sunday)

- Doors of Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (Seetheholyland.net)

- Bas-relief showing Christ being taken to the high priest, in the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (Seetheholyland.net)

- Pilgrims praying in the Sacred Pit under the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (Seetheholyland.net)

- St Peter denies Christ, outside the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (Seetheholyland.net)

- St Peter in anguish after his betrayal (© Tom Callinan / Seetheholyland.net)

- Hole providing access to the Sacred Pit under the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (Seetheholyland.net)

- St Peter faces Christ after his denial, in the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (Seetheholyland.net)

- In the Sacred Pit under the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (Seetheholyland.net)

- Christ in captivity, in the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (Seetheholyland.net)

- St Peter later declares his love for Jesus, by the Sea of Galilee (Seetheholyland.net)

- Description of caves under the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (© Tom Callinan / Seetheholyland.net)

- Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (Seetheholyland.net)

- Christ being insulted in the House of Caiphas (Seetheholyland.net)

- Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (Seetheholyland.net)

- Description of the Sacred Pit under the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (© Tom Callinan / Seetheholyland.net)

- Byzantine crosses under the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (Seetheholyland.net)

- Steps leading to the House of Caiphas (Seetheholyland.net)

- Interior of Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (Seetheholyland.net)

- Christ in a rope harness, on an outside wall of the Church of St Peter in Gallicantu (Seetheholyland.net)

References

Bar-Am, Aviva: Beyond the Walls: Churches of Jerusalem (Ahva Press, 1998)

Brownrigg, Ronald: Come, See the Place: A Pilgrim Guide to the Holy Land (Hodder and Stoughton, 1985)

Gonen, Rivka: Biblical Holy Places: An illustrated guide (Collier Macmillan, 1987)

Mackowski, Richard M.: Jerusalem: City of Jesus (William B. Eerdmans, 1980)

McCormick, James R.: Jerusalem and the Holy Land (Rhodes & Eaton, 1997)

Martin, James: A Pilgrim’s Guide to the Holy Land (Westminster Press, 1978)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Pixner, Bargil: With Jesus in Jerusalem – his First and Last Days in Judea (Corazin Publishing, 1996)

Wareham, Norman, and Gill, Jill: Every Pilgrim’s Guide to the Holy Land (Canterbury Press, 1996)

External links