Jerusalem

The Monastery of the Cross is one of Jerusalem’s lesser-known gems, although its claimed connection to the cross on which Jesus was crucified may belong more to legend than to reality.

Bell tower dominating Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

The fortress-like appearance of buttressed walls and high windows confirm that its location in the Valley of the Cross was originally an isolated site outside the protective walls of the city.

Now the monastery and its adjacent parkland in West Jerusalem are surrounded by Israel’s Knesset (Parliament) to the north, the Israel Museum to the west, the upmarket Rehavia neighbourhood to the east, and four-lane highways on the south and east.

The monastery’s name comes from a traditional belief that the wood of Jesus’ cross came from a tree planted here in ancient times.

The most common account says Lot planted the tree, but another version involves Adam.

The monastery appears to have been founded no later than the 5th century, though no two sources agree on who founded it.

Some credit the emperor Constantine, his mother St Helena or King Mirian III of Georgia.

It was rebuilt in the 11th century by the Georgian monk Prochorus, on the remains of an earlier structure destroyed by the Persians. Occupied by hundreds of monks, it became the religious and cultural centre for Georgians living in Palestine.

In 1685, with Georgia in decline and subjugated by the Persians and Ottomans, the monastery was taken over by the Greek Orthodox, who restored and repaired it in the 1960s and 70s.

Georgian epic poem was written here

A haven of quiet in busy Jerusalem, the Monastery of the Cross seems to have changed little in centuries.

The complex contains a chapel, living quarters for monks, several courtyards, a small museum with exhibits illustrating monastery life in the past, the old refectory and kitchen, a coffee shop and a gift shop.

In the chapel, a basilica with a central dome, the walls and pillars are decorated with frescoes from the 12th and 17th centuries. The iconostasis separating the sanctuary from the nave contains many icons and paintings.

To the right of the altar is a mosaic floor, all that remains of a 5th-century church destroyed by the Persians in 614.

One of the frescoes commemorates Georgia’s national poet, Shota Rustaveli, who lived in the monastery in the early 13th century and wrote the epic poem The Knight in the Panther’s Skin.

In 2004 an unknown vandal scratched out Rustaveli’s face and part of the accompanying inscription — a fate that had also been suffered by other Georgian artworks in the monastery during the preceding decades.

Frescoes tell story of the tree

On the left side of the chapel, a doorway leads to the heart of the monastery.

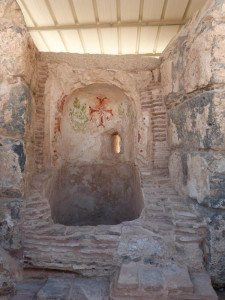

A narrow passageway with displays of old vestments in glass cabinets leads to a darkened chapel. Beneath the altar, a circular plate surrounds the place where the tree of the cross is supposed to have stood.

Beside it is a repository for photographs of people who are sick or in need of help, for whom prayers are being offered.

Heavily-restored medieval frescoes on the walls tell the story of the tree.

First, Abraham is shown with three heavenly visitors (Genesis 18:1-15) who give him three staffs, of cedar, cypress and pine. After Sodom is destroyed, Abraham gives the staffs to his nephew Lot.

Lot plants the staffs and waters them from the Jordan River. The three woods grow into a single tree.

Centuries later the tree is cut down and a beam prepared for the cross.

Administered by: Confraternity of the Holy Sepulchre (Greek Orthodox)

Tel.: +972 52-221-5144

Open: Apr-Sep, Mon-Sat 10am-5pm; Oct-Mar, Mon-Sat 10am-4pm

- Wood from the tree being used for the Crucifixion (© Chad Emmett)

- Monastery of the Cross bell tower (Seetheholyland.net)

- Courtyard in Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Courtyard in Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Iconostasis in chapel of Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Twin cypress trees, brought from Mount Athos in Greece, tower over Monastery of the Cross compound (Seetheholyland.net)

- Well in Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Courtyard in Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Frescoe of St Peter (left) and St Paul in Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Colourful cafe seating in Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Bell tower and dome atop Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Refectory table where monks ate in Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Painting of Lot watering the tree in Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Artworks and nun mannequins in Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Entrance to Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Bell tower dominating Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Strongly-fortified Monastery of the Cross (Sir Kiss)

- Monastery of the Cross from access road (Seetheholyland.net)

- Georgian (left) and Greek inscriptions above entrance to chapel in Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Sequence of paintings beginning with Abraham and his three visitors (Seetheholyland.net)

- Icon of Mary and Jesus in Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Greek Orthodox patriarch’s chair in Monastery of the Cross chapel (Seetheholyland.net)

- Frescoes on pillars in Monastery of the Cross chapel (Seetheholyland.net)

- Portrayal of Crucifixion in Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Disc under altar marking supposed site of the tree in Monastery of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

- Frescoes on pillars in Monastery of the Cross chapel (Seetheholyland.net)

References

Bar-Am, Aviva: Beyond the Walls: Churches of Jerusalem (Ahva Press, 1998)

Bourbon, Fabio, and Lavagno, Enrico: The Holy Land Archaeological Guide to Israel, Sinai and Jordan (White Star, 2009)

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Gonen, Rivka: Biblical Holy Places: An illustrated guide (Collier Macmillan, 1987)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Prag, Kay: Jerusalem: Blue Guide (A. & C. Black, 1989)

Rossing, Daniel: Between Heaven and Earth: Churches and Monasteries of the Holy Land (Penn Publishing, 2012)