Jerusalem

The Church of St Mark is home to one of Jerusalem’s smallest and oldest Christian communities, but it is the setting for a remarkable set of traditions — including the claim to be the site of the Upper Room of the Last Supper.

Entrance to St Mark’s Church (Kudumomo)

This hard-to-find Syriac Orthodox church is in the north-eastern corner of the Old City’s Armenian Quarter, on Ararat Street which branches off St Mark’s Street.

Its worship employs the oldest surviving liturgy in Christianity, based on the rite of the early Christian Church of Jerusalem. The language used is Syriac, a dialect of the Aramaic that Jesus spoke.

St Mark (also known as John Mark) came from Cyrene in Libya. He became a travelling companion and interpreter for St Peter, and used Peter’s sermons when he composed the earliest of the four Gospels.

Mark’s mother, Mary of Jerusalem, had a house where members of the early Church met. It was to this house that Peter went when an angel released him from prison (Acts 12:12-17).

The Syriac Orthodox believe the Church of St Mark is on the site of that house — a belief supported by a 6th-century inscription discovered there in 1940.

Variety of events claimed

By associating the Church of St Mark with the Upper Room, the Syriac Orthodox believe it was the location of these events:

- The Last Supper (Mark 14:12-25)

- The election of Matthias as an apostle to replace Judas Iscariot (Acts 1:21-26)

- Post-Resurrection appearances of Jesus to the disciples, including the one in which he showed doubting Thomas the wounds in his hands and side (John 20:24-28).

- The coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost (Acts 2:1-4)

While there is oral tradition to support these claims, scholars generally accept that the Upper Room was on the site of the Cenacle, near the summit of Mount Zion.

Another Syriac Orthodox tradition holds that the Church of St Mark is at the place where Mary, Jesus’ mother, was baptised. A baptismal font purportedly used can be seen inside the church.

The church also displays a painting on leather of Mary and Jesus. It is said to have been painted by St Luke, but experts date it to the early Byzantine period.

Inscription identifies ‘house of Mary’

A notice beside the door proclaims the Church of St Mark to be “The first church in Christianity”, in the belief that it is on the site of the original house-church of Jerusalem’s early Christians.

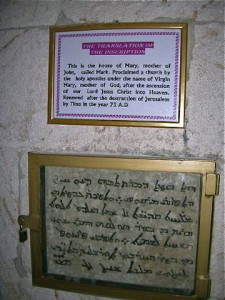

Just inside the entrance, set into a pillar, is an inscribed stone discovered during a restoration in 1940. Its inscription, believed to be from the 6th century, is in ancient Syriac. It says:

“This is the house of Mary, mother of John, called Mark. Proclaimed a church by the holy apostles under the name of Virgin Mary, mother of God, after the ascension of our Lord Jesus Christ into heaven. Renewed after the destruction of Jerusalem by Titus in the year AD 73.”

The interior of the church is dark, but the decoration is ornate. The sanctuary is richly embellished, though often partly hidden by a curtain representing the veil in the Temple.

The present church was built in the 12th century over the ruins of a 4th-century church. Steps lead down to a crypt, believed to have been the lower floor in the house of Mark’s mother.

First native people to adopt Christianity

The Syriac Orthodox Church claims St Peter as its first patriarch, in Antioch in AD 37. The word “Syriac” is not a geographic indicator, but refers to the use of the Syriac language in worship.

Syriac Christians see themselves as the first people to adopt Christianity as natives of the Holy Land. At the time of Christ, the Roman province of Syria included today’s Syria, Lebanon, most of Palestine, and parts of Jordan and Turkey.

Often called “Jacobites” (after an early bishop), the Syriac Orthodox form one of the Oriental Orthodox churches that became separated from the mainstream of Christianity in the 5th century over a disagreement about the nature of Christ. They are not in communion with either Constantinople or Rome.

Their community in Jerusalem, centred on the Church of St Mark, numbers only about 600.

The Syriac Orthodox also worship in the Chapel of St Joseph of Arimathea and St Nicodemus in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

In Scripture:

The Last Supper: Mark 14:12-25

Matthias is elected to replace Judas Iscariot (Acts 1:21-26)

Jesus shows Thomas the wounds in his hands and side (John 20:24-28).

The coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost (Acts 2:1-4)

Peter goes to the house of Mark’s mother: Acts 12:12-17

Administered by: Syriac Orthodox Patriarchal-Vicariate of Jerusalem and Jordan

Tel.: 02 628-3304 or 052 509-0478

Open: Apr-Sep 9am-5pm; Oct-Mar 7am-4pm; Sunday 11am-4pm

- Pilgrims outside Church of St Mark (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

- Entrance to St Mark’s Church (Kudumomo)

- Claim to be “The first church in Christianity” (Seetheholyland.net)

- Painting attributed to St Luke (© Fili Feldman)

- Inscription from 6th century (© Israelseen.com)

- Interior of St Mark’s Church (© Fili Feldman)

- Chapel with painting attributed to St Luke (© Fili Feldman)

References

Bar-Am, Aviva: Beyond the Walls: Churches of Jerusalem (Ahva Press, 1998)

Brownrigg, Ronald: Come, See the Place: A Pilgrim Guide to the Holy Land (Hodder and Stoughton, 1985)

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Gonen, Rivka: Biblical Holy Places: An illustrated guide (Collier Macmillan, 1987)

Hilliard, Alison, and Bailey, Betty Jane: Living Stones Pilgrimage: With the Christians of the Holy Land (Cassell, 1999)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Prag, Kay: Jerusalem: Blue Guide (A. & C. Black, 1989)

Shahin, Mariam, and Azar, George: Palestine: A guide (Chastleton Travel, 2005)

Wareham, Norman, and Gill, Jill: Every Pilgrim’s Guide to the Holy Land (Canterbury Press, 1996)

External links

St Mark’s Monastery (Syriac Orthodox Resources)

Syrian Orthodox Church in Jerusalem (YouTube)